The village of Jaladihi in Odisha’s Keonjhar district, is nestled in the heart of a lush forest, its undulating topography a testament to nature’s artistry. For generations, the people of this remote hamlet lived in harmony with their surroundings, till modernisation shattered its idyllic existence.

Rain-fed agriculture and forest produce were the lifeblood of Jaladihi, sustaining its inhabitants through countless seasons. Crystal-clear streams meandered through the village, and wells provided ample groundwater for their needs. The elders often reminisced how blessed they were to have such abundance in their humble abode.

Modernisation takes its toll

However, all this became a thing of the past when an iron plant set up operations nearby. The company, in its quest for resources, sank a massive borewell, plunging a thousand metres into the earth. The effects were swift and devastating. The streams that had flowed ceaselessly for centuries began to shrink, eventually drying up altogether. The groundwater level plummeted, leaving the village wells parched.

Panic gripped Jaladihi as the reality of their water crisis set in. The lush green fields that once yielded bountiful harvests now lay barren and cracked. The forest, too, seemed to wilt, its vibrant ecosystem struggling to cope with the sudden scarcity. The very foundation of the lives of Jaladihi’s inhabitants was crumbling beneath their feet.

Pleas for help fall on deaf ears

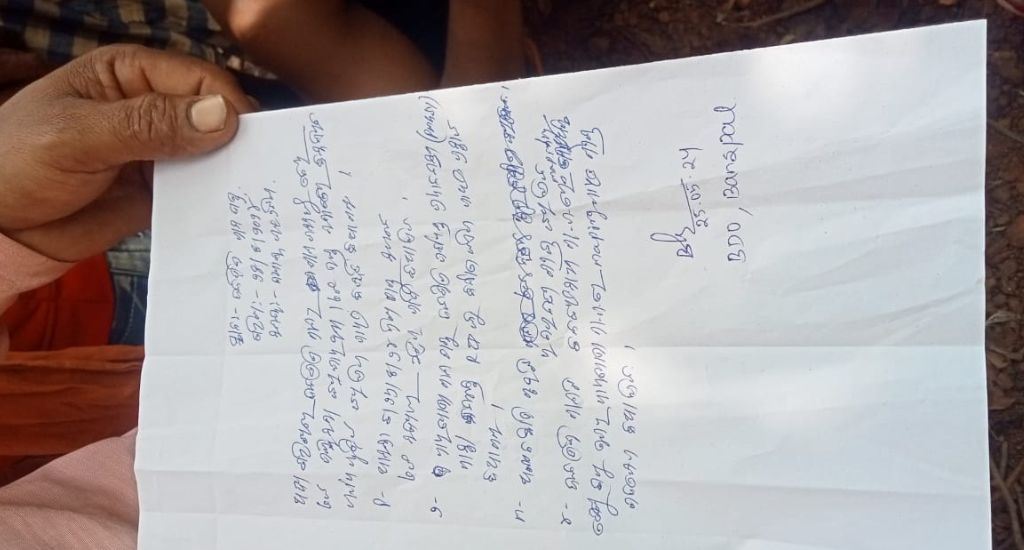

Desperate, the villagers turned to their local panchayat for help. Numerous applications were filed, detailing their plight and pleading for intervention. But their cries fell on deaf ears. The panchayat, overwhelmed and underfunded, could offer little more than empty promises. Undeterred, the people of Jaladihi took their case to the block level, hoping that higher authorities would recognise the urgency of their situation. Yet, time and again, they were met with bureaucratic indifference and inaction.

As months turned into years, frustration and despair took root in Jaladihi. The once-vibrant community was withering away, much like their beloved forest. Families began to contemplate migration, abandoning ancestral lands in search of water and livelihood elsewhere. The village elders, however, were determined to find a solution. They knew that their collective voice had the power to bring change if only they could make it heard.

More power to the common man

It was during a village meeting, as the Lok Sabha elections loomed on the horizon, that a radical idea took shape. Purandar Mantri, the secretary of the village development committee, proposed a daring plan. “We will boycott the elections,” he declared, his voice trembling with emotion.

Let them see how much our votes matter when not a single ballot is cast from Jaladihi!

he thundered.

The proposal was met with a mix of excitement and trepidation. Some feared retribution, while others worried about the legality of such an action. But as discussions continued late into the night, a consensus emerged. They had exhausted all conventional means of seeking help. It was time for drastic measures.

Word of Jaladihi’s intended boycott spread like wildfire. Local media picked up the story, and soon it became a talking point across the district. Politicians, who had long ignored the village’s pleas, suddenly found themselves in the spotlight. The administration, fearing a public relations disaster, sprang into action.

Call for action

Just on the day of the elections, a convoy of official vehicles made its way along the dusty road to Jaladihi. The tahsildar and the Block Development Officer (BDO) themselves had come to address the villagers’ concerns. As the community gathered in the village square, a palpable tension filled the air.

The officials, acutely aware of the stakes, made a series of promises. “We understand your suffering,” the tahsildar began, adding “We are here to assure you that help is on its way.”

He outlined a plan that would bring immediate relief to Jaladihi. Two tankers would supply drinking water to the village regularly, ensuring no one went thirsty. The BDO had more encouraging news. “We have decided to divert funds from the District Mineral Foundation to your village,” he announced. “This money will be used to dig farm ponds for surface water storage and groundwater recharge. It’s a long-term solution that will help restore the water balance in your area,” he said.

The villagers listened intently, years of disappointment making them cautious about getting their hopes up. Yet, as the officials concluded their speech with firm timelines and accountability measures, a glimmer of hope began to shine through the cloud of despair that had hung over Jaladihi.

The political will of the people

As the convoy departed, leaving behind a trail of dust and promises, the people of Jaladihi gathered once more. They debated long and hard about whether to go ahead with the boycott or to give the system one last chance. In the end, they decided to cast their votes, but with a renewed sense of empowerment and vigilance.

The water tankers arrived the very next day, bringing much-needed relief to the parched village. As the weeks passed, work began on the farm ponds, slowly but surely breathing life back into the land. The forest, too, seemed to respond, its leaves a little greener, its streams a little fuller.

Jaladihi’s struggle was far from over, but its people had rediscovered their voice. They had shown that even the smallest village could stand up and demand its rights. As they looked to the future, they knew that their unity and determination would see them through whatever challenges lay ahead.

The lead image on top depicts the iron plant at Jaladihi that allegedly plunged the village into a water crisis. (Photo by Saswatik Tripathy)

Kartik Chandra Prusty is a team leader at the Foundation for Ecological Security, Keonjhar.

Saswatik Tripathy works as a senior project manager at the Foundation for Ecological Security Keonjhar.