Bayalu Chitralaya: Karnataka village eyes reclaiming artistic past

Plans are afoot to make Sonangeri host art and artists where an experiment to make the walls of the village an art canvas in the 1990s had a huge success.

Plans are afoot to make Sonangeri host art and artists where an experiment to make the walls of the village an art canvas in the 1990s had a huge success.

Nestling in the foothills of the Western Ghats, Sonangeri in Dakshina Kannada district of Karnataka might seem like any of the villages that dot India’s vast rural landscape. But then, Sonangeri is no ordinary village.

Despite being inhabited by ordinary villagers leading rather humdrum lives, it enjoys a pride of place in the country’s artistic firmament.

It was here in 1993 that the late artist Mohan Sona gave wings to his creative imagination, turning ordinary village homes into art studios and the entire village into a veritable art canvas.

Thanks to his unique initiative, artists from all over the country came to the village to put paint to their brushes. They lived in the homes of the villages, sharing space and meals with the villagers. They painted during their stay. When they left, they left behind their creations as exhibits in the homes they stayed.

In no time, Sonangeri was transformed into Bayalu Chitralaya, – an open gallery, attracting visitors from far and wide.

Everyone admired the artistic creations that adorned the walls of the village homes. They were meant to be permanent exhibits.

It has been long time since the experiment that conceptualised a whole village as a canvas first put Sonangeri on the Indian art map. It has also been two years since Sona – the prime mover behind the enterprise – passed away.

In the intervening years, Sonangeri has changed. Houses have been altered and refurbished. Some have fallen into disrepair. Several of them have changed hands.

It has meant that many of the paintings that the artists left behind as exhibits have lost their pride of place. Some have been tucked away in the attic. Many among those still hanging on the walls have collected inches of dust.

Fortunately, there is a new push to help Sonangeri reclaim much of its lost lustre as the village of arts.

Mrunali Mohan, Sona’s daughter, is planning to revive her late father’s initiative.

Also Read | Saving Khovar and Sohrai arts of “painted villages”

It certainly is worth reclaiming since the initiative wasn’t just an art camp, but an attempt to bridge the urban-rural gap.

“It helped foster human relationships and my father knew,” Mrunali said.

Helping her in the renewed effort to encourage Sonangeri villagers to host artists is Namitha, Sona’s niece.

“Just like Mrunali, I was very young then. But I grew up around my uncle’s art. I too want to preserve his spirit,” Namitha emphasised.

Though many of the old residents are dead, the response to the revival project is said to have been positive.

The younger generation has heard stories of the experiment that Sona helped Sonangeri craft and are keen to relive it again.

Nostalgia for the heady days gone by is a major motivator. What Sona achieved is part of local village folklore.

“Art is the culture of the metro,” pointed out veteran visual artist Sudesh Mahan. “Even rural artists had to come to the city and exhibit their work. But Sona did something entirely different”

“He convinced nearly 40-50 families [of Sonangeri] to convert their living room into an art gallery. They did not understand art. But they let the artists into their homes, because of their love for Sona,” Sudesh reminisced.

Sona wrote to more than 200 artists to come to Sonangeri. Some 160 responded and came to live and work in the village for a period of 10 days.

The art work they left behind had a far lasting impact.

Also Read | Odisha village continues to keep traditional art alive

“Through Bayalu Chitralaya, Sona gave the artists an opportunity to experience the village that was not only their subject, but also their home,” Mahan added.

“I loved the concept and the idea,” admitted AM Prakash, former principal of Kalamandira School of Art. He was one among the artists who came to work in Sonangeri.

The experience was unique – both for the artists and the villagers.

In a typical art camp, there is very little contact between artists and the local populace. In Sonangeri however, artists had to become a part of the household.

“We were able to look at their food culture, their professional world, their interactions with each other very closely. They wouldn’t hide anything,” Prakash recounted.

The experience was enriching for the villagers too.

They got a rare peek into the lives of artists, even bonding with several who invited the villagers to their weddings.

Niranjan Mittamajalu, a farmer, was a young boy then. He remembers sitting next to artist Venkat Montadka and staring at the canvas. “I was in primary school. It was like a festival. All homes were in a joyous mood.”

For Karunakar Rai, whose family hosted Prakash, it was the artist’s eating habits that he still clearly remembers.

“He was not used to eating boiled rice. But he still insisted on eating what we ate,” he recounted of Prakash, whose abstract work still hangs on the living room wall next to the television set.

The novelty of artists coming to live and leave their creations in Sonangeri created more than a flutter. People came from far and wide and socialised over cultural programmes held every evening.

There were also the odd instances of hostile neighbours burying their hatchet and becoming friends again. Camaraderie of course was the underpinning of Bayalu Chitralaya.

“I think art was the excuse to bring us and them together,” Prakash recollected.

The excuse has not lost its meaning even now, and those like Mrunali are determined to recreate Sonangeri’s Bayalu Chitralaya so that all kinds of divides could disappear with every stroke of the paint brushes.

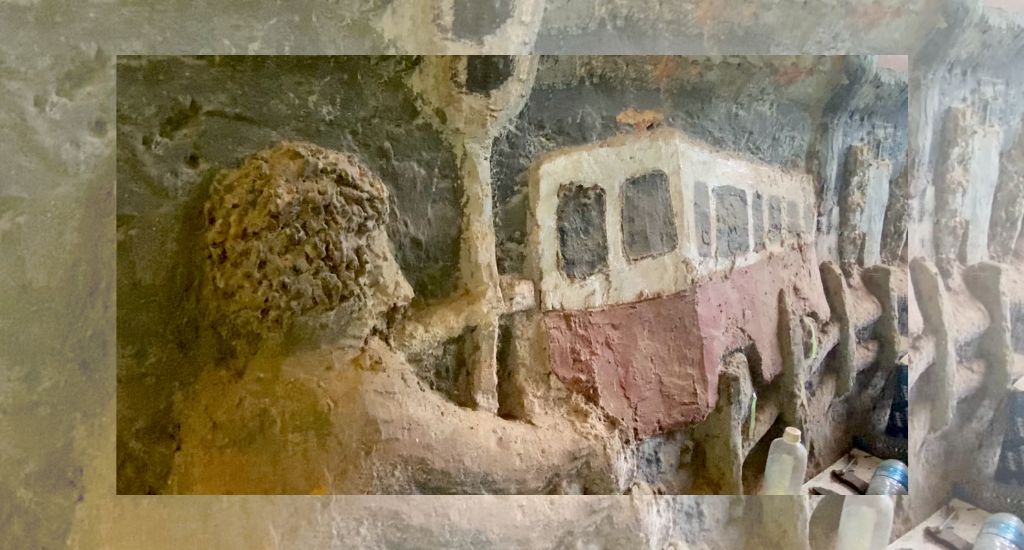

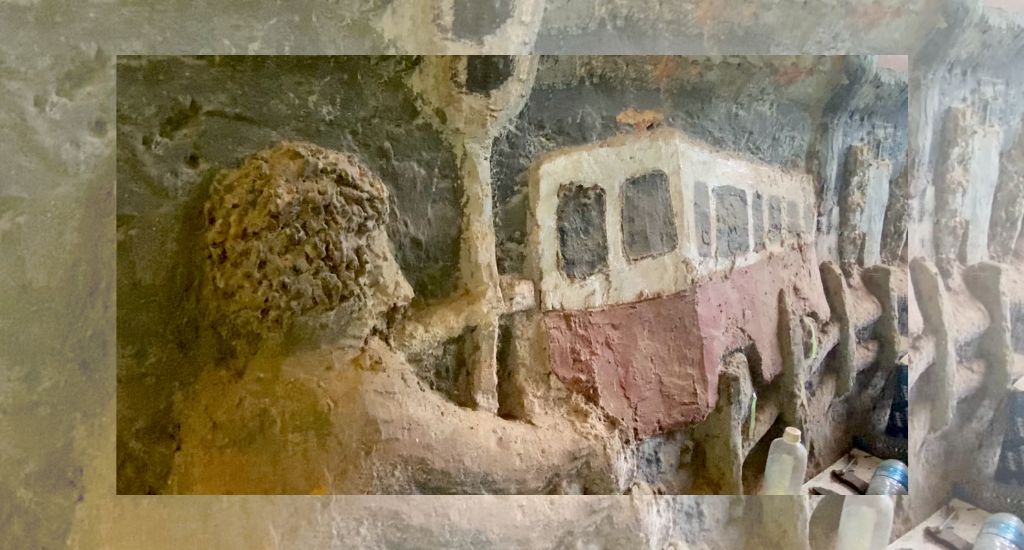

The lead image shows a close-up view of relief sculptures (Photo by Amulya B)

Amulya B is a multimedia journalist, writer and translator based in Bengaluru. Her stories explore the intersection of culture, society and technology. She is the winner of Toto Funds the Arts for creative writing and Laadli Award. She is a Rural Media Fellow 2022 at Youth Hub, Village Square.