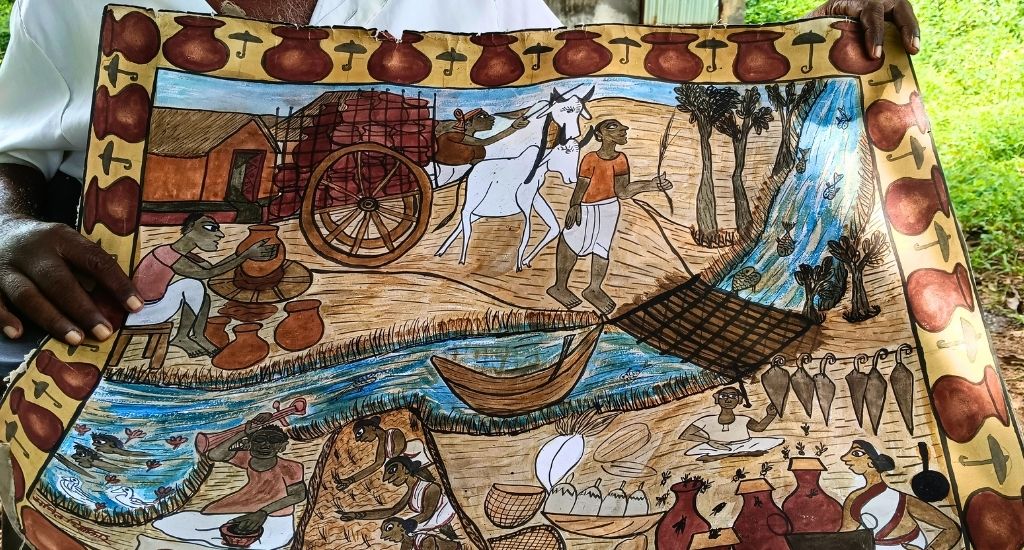

Why is Jharkhand’s Paitkar scroll art losing colour?

Paitkar scroll paintings of Jharkhand are silently fading into oblivion due to waning interest in the art form among enthusiasts and the apathy of authorities.

Paitkar scroll paintings of Jharkhand are silently fading into oblivion due to waning interest in the art form among enthusiasts and the apathy of authorities.

The village of Amadubi in East Singhbhum district of Jharkhand basks in proximity to the picturesque Ghatshila town, a favourite haunt for tourists. Yet, unbeknownst to many, this remote corner with its lush hilly backdrop is the home of the illustrious Paitkar paintings of Jharkhand.

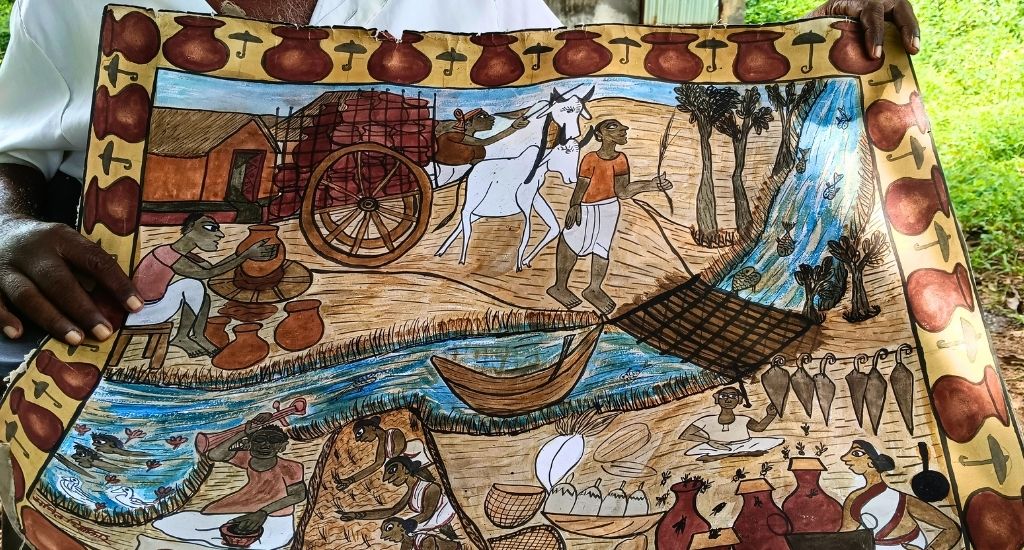

This folk art form intricately weaves tales of life’s origins, tribal existence, Hindu history and legends, rituals, and festivals.

Painted in the traditional scroll style, these artists, also skilled vocalists, employ natural materials such as stones, leaves, flowers, and trees to craft the pigments that give life to their imagination on paper. The tools of their trade, once handcrafted from goat hairs, have since been replaced with brushes readily available in the market.

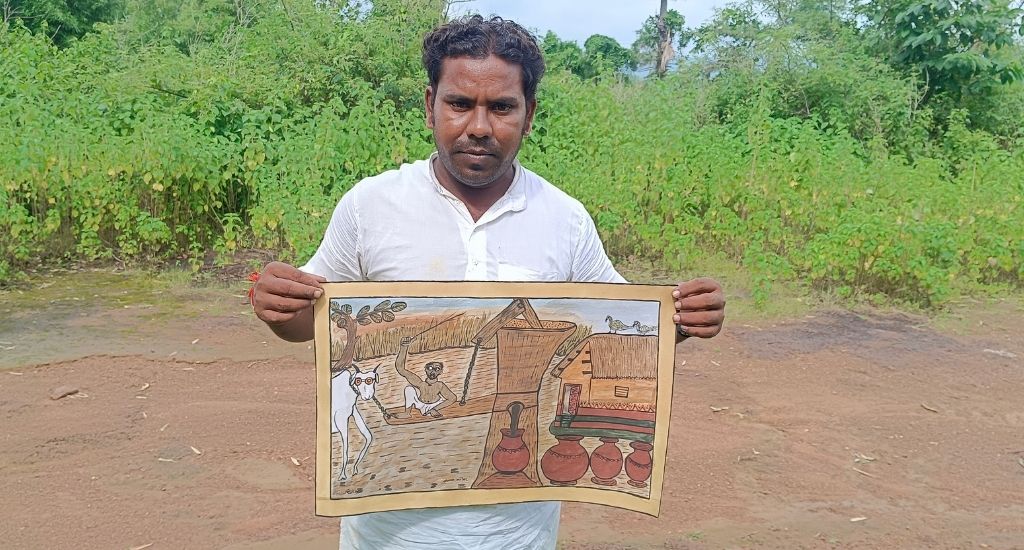

A tight-knit community of around 45 artisans bearing the common surnames Chitrakar (picture makers) and Gayen (singers) are quietly cradling a fading treasure of Amadubi, located about 190km from state capital Ranchi.

Anil Chitrakar, one of the village’s oldest surviving artisans at 71, recounted the art’s historical origins, tracing it back to the time of King Ramchandra Dhal, who reigned over the Dhalbhumgarh region of current-day East Singhbhum.

“Around 22 itinerant artisans landed in his kingdom and were arrested by his men. They were presented before the king and they explained that they were painters and singers who travelled in search of livelihood. Impressed by their performance, the king granted them a permanent land here (now Amadubi) to settle and nurture this art. Since then, our ancestors have thrived in this land,” he said.

Beneath this serene façade, the artisans bemoaned the encroaching shadows of extinction, pinning the blame on the state government and the COVID-19 pandemic for pushing them toward alternative professions.

Several artists in the village have already forsaken their traditional craft, turning to menial jobs to eke out a living.

Also Read: Alu Kurumba art depicts the tribes’ connection with nature

Anil Chitrakar, nearly blind, became emotional when narrating the plight of the Paitkar artists today.

“I have trained around 150 artisans in my life, but in the past eight years, no one has sought training from me. I lost my eyesight a few years ago and had to cease work. I live in a humble mud house, struggling to afford even a square meal a day. My house lacks electricity, and I haven’t received any government aid. Corrupt officials demand bribes for house repairs, which I cannot afford. This is the reality of Paitkar scroll painters,” he said.

Kamal Chitrakar, a 40-year-old artisan who sought employment as a labourer in a private factory in Tatanagar, roughly 60km away, revealed his decision to abandon the art five years ago.

“Many of our paintings gather dust in our homes. There are no buyers. No one has enquired about the art or the challenges we face in the past five years. I was disheartened and had to work as a labourer to sustain myself. Although the income is modest, there is a guarantee of payment, which, unfortunately, we do not have in Paitkar paintings,” he said.

The state government, in collaboration with non-profit organisation Kalamandir, established the Amadubi Rural Tourism Centre in 2013 to promote the art form and attract tourists.

However, artisans argued that it has fallen short of its objectives.

Also Read: Mandala art and Kashmir’s shikara sorceress

“The major issue is the insufficient marketing of the tourism centre, which limits our business. We need better market linkages and government support to enhance our income. I must earn by providing training in local schools and selling my paintings to various social organisations in Jharkhand and neighbouring states,” said Kishore Gayen, a master trainer at the centre.

He said both state and central governments had organised workshops for artisans across the country, allowing them to earn substantial sums – between Rs 15,000 and Rs 20,000 – within ten days. However, these opportunities came to a halt during the pandemic.

Amitava Ghosh, the founder of Kalamandir, rebuffed the notion of the art fading into oblivion and placed some responsibility on the artists.

“The situation is not as dire as portrayed. Some artists earn well, but they have become solely profit-oriented, demanding high prices for their paintings that often deter potential buyers. We have connected them to various national and international platforms to enhance visibility and business. We are also pursuing a Geographical Indication (GI) tag to further promote their art. Over the years, scroll paintings have gained recognition through our concerted efforts,” he said.

As ominous rain clouds envelop the sky and raindrops begin to fall, Anil Chitrakar hurriedly collected his paintings, carefully stowing them in a cloth bag.

“These paintings hold our legacy and should be preserved for future generations. Perhaps one day, they will fetch me a good price,” he mused, his steps quickening to a safer place.

Also Read: Tribal artist creates coat of many colours for PM Modi

The lead image at the top shows a beautiful Paitkar scroll painting (Photo by Gurvinder Singh)

Gurvinder Singh is a journalist based in Kolkata.