Sariska’s herders fear livelihood loss with eviction

Nomadic pastoralists being evicted from Sariska Tiger Reserve to conserve tigers introduced from Ranthambore fear loss of livelihoods, and life in relocation settlements with poor amenities

Nomadic pastoralists being evicted from Sariska Tiger Reserve to conserve tigers introduced from Ranthambore fear loss of livelihoods, and life in relocation settlements with poor amenities

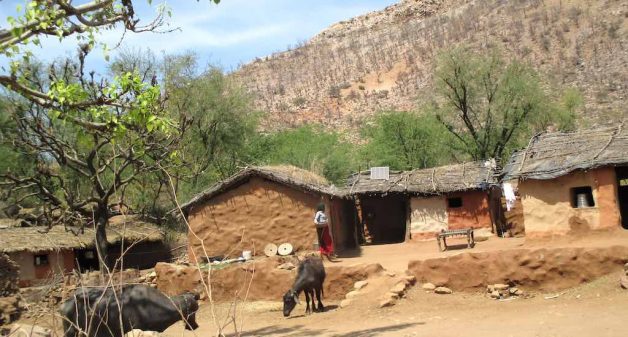

Uganti looked flummoxed and Jagan, her sister-in-law, pensive. Uganti lives in Bera, one of the 29 villages to be relocated to protect the tigers in Sariska Tiger Reserve (STR). The village is in STR’s core area in Umrain administrative block of Alwar district in Rajasthan.

Bera lies by densely forested areas. Most of its residents survive by selling milk and milk products. Presently, majority of the men among the 55 households in the village have left their homes, trekking long distances with their herds of buffaloes, cows and goats, to different places.

They go to Mathura and Etah in Uttar Pradesh, Morena in Madhya Pradesh, Mahendragarh and Rohtak in Haryana, besides Malakhera and Haldina villages in Alwar district, in search of fodder and water for their herds. They return to their village when the monsoon sets in.

Communities facing displacement from villages in the core area of Sariska Tiger Reserve and those already relocated, to conserve introduced tigers, fear losing their traditional livelihood and having to live with poor amenities.

Eviction of forest dwellers

According to Aman Singh, founder of Krishi Avam Paristhitiki Vikas Sansthan (KRAPAVIS), Alwar-based non-profit organization working among the forest dwellers of STR, Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, referred to as Forest Rights Act (FRA) has not been implemented in Alwar district.

Singh said that the forest department has arbitrarily declared 72% (around 881 sq. km) of the total area of 1213.33 sq. km, under the Sariska Project Tiger Area as Critical Tiger Reserve (CTR), without holding consultations or obtaining consent from either the village councils or the villagers.

“Blamed for wiping out tigers from Sariska, the traditional forest dwellers are facing forceful eviction,” Singh told VillageSquare.in. “The FRA provisions for recognition and settlement of rights before village relocation have not been complied with even after they were made mandatory in National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) guidelines.”

Living with tigers

“Our livestock and we have been sharing space and natural resources with wildlife,” said Shisram Gujjar, who was planning to take his herd of goats to Laxmangarh. “Gujjars and other indigenous communities living here have harmonious co-existence, even with the tiger, the top predator of Sariska jungles.”

According to Ratiram, a villager, the tigers in Sariska might have been wiped out even before 2005, and officials might have made false claims till then. “When things got out of hand, we, the forest dwellers, were being blamed as helping poachers,” he told VillageSquare.in.

Ratiram said that they have been living in Sariska, even before it was declared a reserve in 1995. Viren Lobo, an ecologist and livelihood expert, said that the tigers in Sariska were well acquainted with the presence of the traditional forest dwellers.

Making way for tigers

“When tigers were brought from the Ranthambore Tiger Reserve in 2007, to restock Sariska, some of the key issues were not addressed and the newly introduced tigers had more proximity to human beings,” Lobo told VillageSquare.in.

Lobo said that the spread of invasive species and resultant change in floral composition and feeding habits of animal species were being ignored. “If they become attractions in tiger safaris, they will lose their wild characteristics,” said Lobo.

“The latest conservation plan is dedicated to make the reserve a safari park for revenue generation than forest resource development,” said Lobo. “Government-regulated display of tigers to tourists is given prime importance than community-oriented conservation and management of the entire wildlife of the reserve.”

Buffer zone contentions

Aman Singh said that the residents of Kalikhol village have farming and grazing rights, as the village falls in buffer area of Sariska. In January 2019, when the community started restoration of a johad, a traditional rainwater harvesting system, ahead of the monsoon, the forest department stopped the work, and asked for the map of the revenue land, and copy of record of rights of the village.

All the villagers from Umri and Deori and some from Kiraska have been relocated to Maujpur Roondh (temporary pastoral settlements). Maujpur Roondh has a mixed composition of Meenas and Gujjars. Residents of the remaining 26 villages are yet to be relocated.

Relocated 80km from Sariska reserve, the Meenas are from Deori village and Gujjars from Umri village. It’s close to Armed Border Force or Sashastra Sena Bal’s (SSB) training and recruitment center and hence the relocated settlers fear another displacement.

The Meena hamlet of Maujpur Roondh village has cemented roads. Meenas, as an agrarian community, agreed to be relocated. “We presumed that we would be able to farm without restrictions from the forest department, and get a better education for our children,” Bhola Ram Meena told VillageSquare.in.

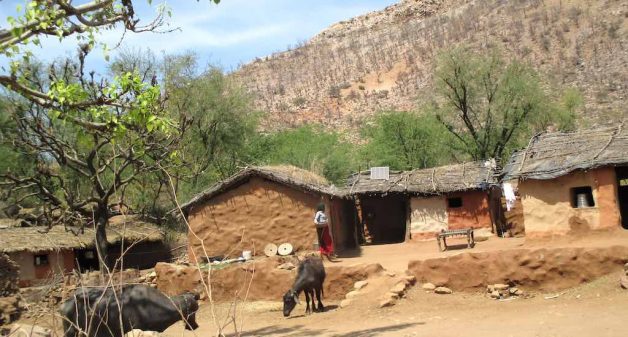

In Maujpur Roondh, a dusty road – markedly different from the road to the Meena hamlet – leads to the Gujjar hamlet of 55 households. Kishen Gujjar (60) said that they are pastoralists, whose village Umri was close to the entrance of the Sariska reserve.

Relocation compensation

Bhola Ram Meena, who is in Maujpur Roondh, said that his four brothers are still in Deori. “They have rejected the relocation package as they would get only cash of Rs 10 lakh as compensation, and 10% would be deducted for community facilities,” he told VillageSquare.in.

However the relocation package prescribed by National Tiger Conservation Authority offered two options. The first option is payment of the entire package amount of Rs 10 lakh per family without any rehabilitation process.

The second one is relocation/rehabilitation package at Rs. 10 lakh per family (consolidating five categories as percentage of total package), two hectares of agriculture land , procurement and development (35%), settlement of rights (30%), homestead land and house construction (20%) and incentives (5%). The community facilities component is 10%, which would be deducted from relocation package.

Loss of traditional livelihood

According to Kishen Gujjar, earlier he could take his animals far to graze, but later the forest department started accusing the villagers wrongfully and so they decided to move. But most of them lost livestock as there was not enough water.

He pointed out that the 10% deducted for community facilities would mean Rs 55 lakh for the Gujjar hamlet. “But see the condition of the road; also we have intermittent power outage,” he said. Grazing their livestock is also difficult as residents of the other villages raise objection. Kishen Gujjar also said that the schools are quite far from their village.

“Circumstances forced us adapt to farming so that we don’t die of hunger,” Kishen Gujjar told VillageSquare.in. “Forest department gave us adhikar patra but we have no ownership rights. We cannot get loans with this, if we need funds to buy tractor or other materials to farm in a better way.”

Tarun Kanti Bose is a New Delhi-based journalist. Views are personal.