Adivasis in Odisha suffer the most due to malnutrition

Malnourished tribal communities in Odisha have not benefitted from decades-old government schemes aimed at improving health outcomes, mainly due to patchy and apathetic implementation

Malnourished tribal communities in Odisha have not benefitted from decades-old government schemes aimed at improving health outcomes, mainly due to patchy and apathetic implementation

“Last year, my 6-month-old son suddenly came down with high fever and died before we could reach the local primary health center,” said Sundri Majhi, a native of Haridakut village in Mayurbhanj, the district in Odisha with the highest population of tribes. “We don’t know what killed him.”

Odisha has the largest number of adivasi or tribal communities, 62 to be precise, in India, including 13 particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs). The state has a tribal population of 9.59 million, constituting 22.86% of the total population, according to Census 2011. At 1.48 million and 58.7%, respectively, Mayurbhanj district has the highest tribal population and highest proportion of tribes.

Around 57% of under-five tribal children are chronically undernourished, according to United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Infant mortality among tribal communities in Odisha is 92, as against the national average of 84. The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme could play a vital role to reverse the grave situation.

Integrated Child Development Services

The ICDS scheme is one of the flagship programs launched by government of India in 1975 to combat malnutrition and ill health of children under six years of age, besides expectant and young mothers. However, the results have not been satisfactory across India.

Several studies have revealed that the scheme has not been implemented effectively. Large-scale corruption and irregularities of food supply has plagued the program.

The Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) report released in 2017 found lacunae in the implementation of ICDS scheme at the state. The state-level monitoring and review committee, headed by the chief secretary, had met thrice during 2011-16, against the mandate of holding a meeting at least once every six months.

Poor infrastructure

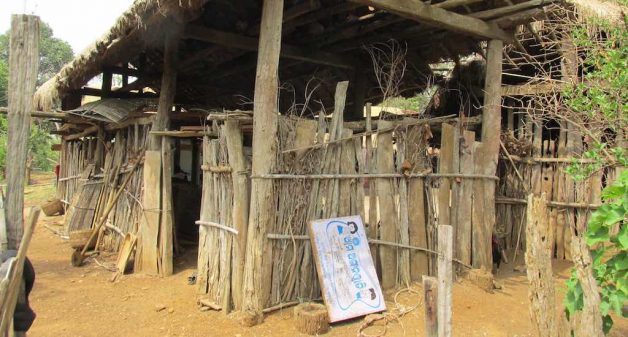

Anganwadis serve as the principal centers for implementation of ICDS services, primarily supplementary nutrition and pre-school education. In March 2011, the Government of India had mandated that an anganwadi center (AWC) must have a separate sitting room for children and women, a kitchen, a store room for provisions, child-friendly toilets, drinking water facility and a play area.

But the AWC in Haridakut village is running in a dilapidated hut. “You can see the poor condition of the center for yourself,” Ghasiram Majhi, a native of the village, told VillageSquare.in. “In rainy days we cannot send our children to the anganwadi.”

According to the CAG report, out of 71,306 AWCs in the state, only 28,187 (40%) had dedicated ICDS buildings. “There is no separate kitchen in our center, therefore we cook in the open,” the anganwadi worker told VillageSquare.in.

Poor quality food

There have been instances of short supply or non-supply of eggs and Take Home Ration (THR) of rasi laddoo or sesame balls, due to mismanagement. “There are several cases of supply of adulterated or sub-standard chhatua made of roasted gram, due to poor quality control mechanism,” Srinibas Das, a Koraput-based development professional told VillageSquare.in.

The objective of the supplementary nutrition program (SNP) of ICDS is to bridge the protein-energy gap between the recommended dietary allowance and average dietary intake of children, pregnant women and lactating mothers.

The program entails special supplementary feeding of severely malnourished children and referral to health centers. Residents of Haridakut village hardly receive such referral services.

Irregular health check-up

The health check-up of children is extremely low and that of pregnant women and nursing mothers is also significantly low, according to the CAG report. Children below the age of three need to be weighed once a month and those between three and six years of age need to be weighed every quarter, as per the guidelines.

Such regular monitoring helps the health department staff detect growth deficiency and assess nutritional status of the children and categorize them as normal, moderate or severely malnourished.

According to the villagers of Haridakut, officials check weight once in four or five months. As per ICDS guidelines, every AWC should have kits containing medicine for diarrhea, de-worming, skin disease, etc. However, no such medicine kit is available in the AWC of Haridakut.

“Three years back, I lost my daughter, when she was four months old,” Parvati Majhi of Haridakut told VillageSquare.in. “She was very weak when born, even unable to drink my milk.” The doctor had said that the baby died due to pneumonia.

“In the last two years, many children of our village died due to malnutrition,” Bajuram Ho, a tribal leader, told VillageSquare.in. “Media do not report most of these cases.” He said that there were some cases of measles too.

Positive initiatives

“There is a need to scale up proven nutrition interventions during the first 1,000 days of life, increasing access to essential nutrition services,” said Das.

In 2015, Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiatives (APPI) and the Odisha government started a program to bring down malnutrition in the state. In 2017, the state government, in partnership with APPI and UNICEF, extended the Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) to all the 30 districts.

“Children with acute malnutrition will be treated with Ready to Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) and Energy Density Therapeutic Food (EDTT) through AWCs,” said Prasant Kumar Reddy, director of Social Welfare Department.

The CMAM model was initially piloted in Sudan in 2001 and adopted as an emergency intervention in a country that has a high rate of acute malnutrition exceeding the emergency threshold. Instead of merely replicating the model, the state government of Odisha should give priority to modify CMAM to suit local conditions.

Abhijit Mohanty is a Delhi-based development professional. He has worked with the indigenous communities in India and Cameroon especially on the issues of land, forest and water. Views are personal.