Ladakh’s age-old chuspon water-use system gives hope

As the surge of tourism threatens to tip the fragile balance in Ladakh, hope exists in villages like Sakti on the outskirts of Leh, where traditional systems continue to govern land and water use.

As the surge of tourism threatens to tip the fragile balance in Ladakh, hope exists in villages like Sakti on the outskirts of Leh, where traditional systems continue to govern land and water use.

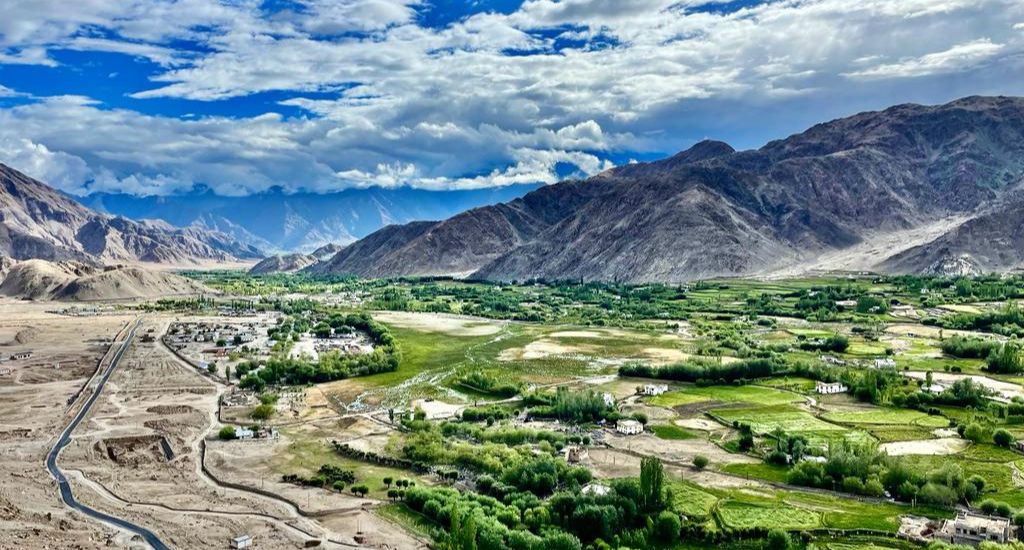

Air? Rarefied. Water? Scarce. Land? An arid and rugged remoteness cocooned by the formidable Himalayas that extend their majestic embrace towards the heavens. Ladakh is a land of barren beauty — a pristine expanse graced by the unspoiled hand of nature but with water crisis.

However, the bustling centre of this captivating landscape — the brick-and-mortar town of Leh — finds itself on the precipice of peril. From being a tranquil outpost for ages, Leh has become a predictable pocket of “overtourism” in the 21st century.

Tourism is both a boon and a bane because the industry is a source of jobs and prosperity, bringing hard currency to many locals who desperately need it. But the two-edged sword also threatens to inflict grievous wounds upon the fragile ecosystem of this town and Ladakh’s other touristy hotspots.

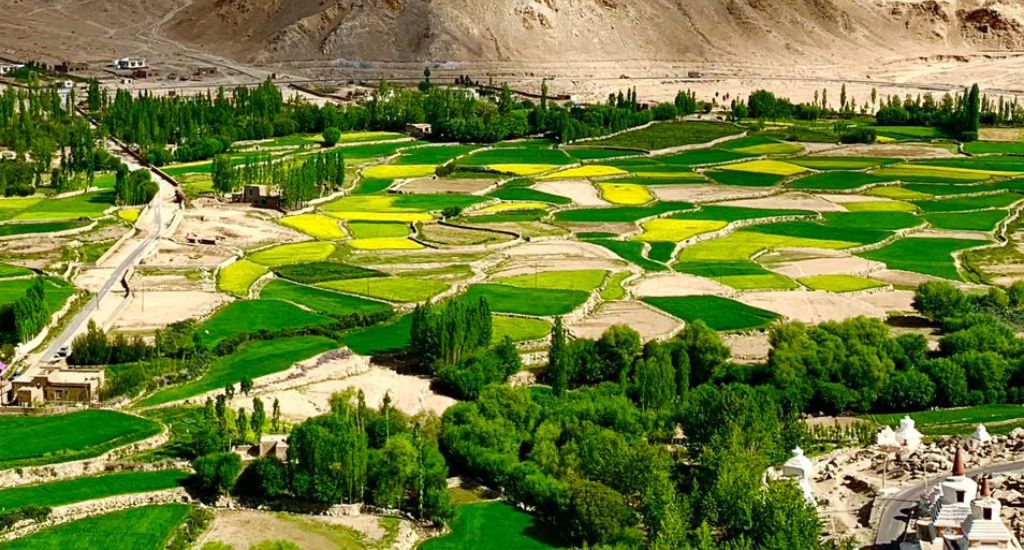

Yet, a mere few kilometres beyond the city limits, the quaint village of Sakti holds out hope through its time-honoured and traditional system of land and water use. Sakti remains an untouched sanctuary, shielded from the heavy hand of tourism’s advance.

Sakti, one of the largest villages in the region with around 400 households, has clung to its roots and withstood the tempestuous winds of change. The villagers still rely on traditional agriculture, their lifeline being the Gang-chu, meltwater from glaciers. It’s nestled between Chang La and Wari La, and the meltwater from these two major passes lets the land flourish with mountain grasslands and fertile fields.

One tradition that has weathered the test of time is the election of a “water lord” — called “chuspon” in the local language. It’s a portmanteau of “chu” meaning water and “spon” denoting lord.

Also Read: Dwindling snowfall leading to water crisis in Ladakh

Inhabiting a high-altitude, cold, arid zone with a short cultivation season, Sakti’s residents have devised local systems that maximise resource usage while minimising conflict. Like any social institution, the chuspon system allows the farming communities to use their land and water resources judiciously, leading to greater prosperity.

The election of the water lord is a crucial component of the village’s traditional festival, facilitating local governance, maintenance and equitable distribution of precious water resources.

“Chuspon are annually appointed at the beginning of the agricultural season. Historically, villagers unanimously elected a man in the community with extensive knowledge of customary duties, rights and responsibilities related to water management. Nowadays, it is appointed on a rotational basis,” said Tsering Dorjay, a former chuspon.

In Ladakh, self-sufficient agricultural systems are intertwined with religious ceremonies that invoke blessings from local deities, fostering a harmonious relationship with nature.

Dorjay, 67, described the tradition of electing a chuspon: “The day is marked with ceremonies and prayers. Lamas from the nearest monastery, Dakthok, are consulted for an auspicious date, and communal meetings are held. It is no less than any other cultural affair.”

However, the task of a chuspon is not for the faint-hearted.

Also Read: Dry toilets to help Ladakh in organic farming

“The tasks are overwhelming and challenging. A chuspon must monitor the water reservoir from 8pm to 3 o’clock in the morning, ensuring water distribution (irrigation) and harmony among farming communities. Therefore, the role mostly falls on men,” said Tsewang Namgail, a 62-year-old retired serviceman.

Agriculture in Ladakh — a land of long freezing winters — hinges on a short growing season during which Gang-chu, or glacial meltwater, plays a pivotal role. Every Ladakhi village features a community water reservoir called zing, where meltwater is collected directly for irrigation. These reservoirs are connected to water canals called yura, which supply water to the fields.

“A chuspon is responsible for managing water distribution, irrigation turns, overseeing zing maintenance, resolving water disputes, and ensuring equitable water distribution among all village families without personal bias or favouritism,” said Namgail.

Sakti’s chuspon tradition exemplifies how a community resource like water is effectively self-governed by villagers, codified into distinct rules and regulations that everyone adheres to. This traditional system, orally passed down through generations, represents a unique community-led, self-governing model. However, the youth, growing up in suburban settings, are increasingly getting disconnected from their agricultural heritage.

Padma Dolkar, a 54-year-old farmer, reflected on the potential loss of this cherished tradition, saying: “It is doubtful whether the youth these days will continue with the tradition and engage in farming. It will be a significant loss if chuspon becomes another lost tradition in the coming years.”

Also Read: Once a ‘burden’, double-humped camel is a prized animal in Ladakh today

The lead image at the top shows a view of the Sakti village from Chemdray monastery. (Photo by Dawa Dolma)

Dawa Dolma is a freelance journalist based in Leh. She writes about climate change, communities, and culture of the Himalayas. She was a Rural Media Fellow 2022 at Youth Hub, Village Square.