Ancient Mayurbhanj Chhau dance steps up revival

The dramatic 19th century martial arts Mayurbhanj Chhau dance is stepping up its revival thanks to renewed patronage of an erstwhile royal family and government support.

The dramatic 19th century martial arts Mayurbhanj Chhau dance is stepping up its revival thanks to renewed patronage of an erstwhile royal family and government support.

What happens to a cultural tradition or art that was started and patronised by royalty after such monarchs no longer rule? Most fade away from collective memory until they are well and truly lost.

Which is almost what happened to the Mayurbhanj Chhau dance.

Until the state government, stepped up to revive the dramatic dance in 2016.

The dance form received another boost when the erstwhile Mayurbhanj royal family turned their Belgadia Palace into a hotel in 2019 and got the Chhau dancers to perform for the tourists.

Mayurbhanj was a princely state until it became a part of the state of Odisha on January 1, 1949.

“My great-great grandfather Maharaja Krishna Chandra Bhanj Deointroduced Chhau during his reign in 1855,” said Akshita M Bhanj Deo of the erstwhile Mayurbhanj royal family.

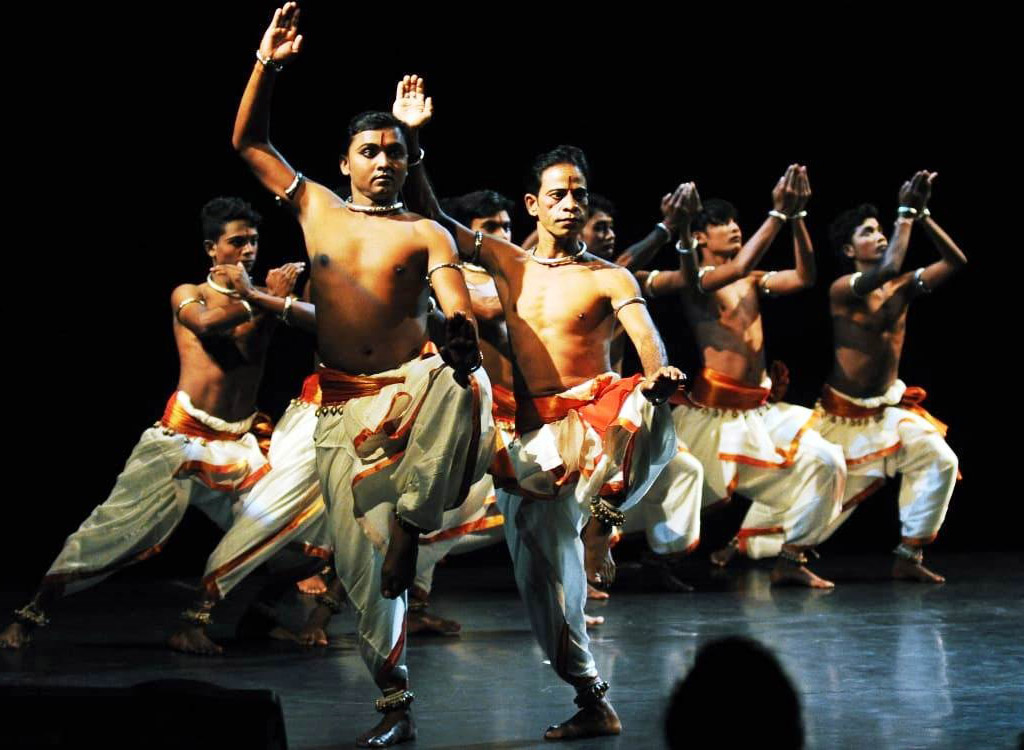

A mix of classical and martial art forms, the dance is performed to the accompaniment of folk and classical music.

Chhau’s origin is believed to be the military camps where Chhau kept soldiers active and entertained during wars. The Mayurbhanj Chhau is one of the three Chhau dances, the other two being West Bengal’s Purulia Chhau and Jharkhand’s Seraikela-Kharsawan Chhau.

In Mayurbhanj Chhau, male members of the Bhokta community performed the dance on Chaitra Sankranti – a festival marking the start of a new year. In preparation the dancers would fast for 13 days before their performance.

The dancers, clad in traditional dhoti, performed episodes from the epics and puranas.

The Mayurbhanj Chhau once had 200-plus dance forms, including solo, duet and group performances. Now only 30 forms are practised.

Both the loss of royal patronage after independence and lack of adequate government support led to the decline of Chhau.

Competing against other entertainment forms through television and the internet led to further decline.

To revive the art of Mayurbhanj Chhau dance the district administration and well-known dancer Subhashree Mukherjee, who had earlier worked with Chhau artists, launched Project Chhauni in 2016.

As part of the initiative, the Mayurbhanj Chhau performing unit was started. Hundred dancers were selected after an intense audition.

Today, Project Chhauni is a registered trust. In 2018 it received a one-time government funding of Rs 1 lakh.

Now 42 dancers are part of the Mayurbhanj Chhau performing unit, which shows there is still room to grow.

“The most distinguishing feature of Mayurbhanj Chhau is the dancers don’t use masks – unlike in the other two forms. Masks are used only for animal characters,” said Bibhudatta Das, director, Project Chhauni.

With the Mayurbhanj Chhau dance having such unique aspects, more should be done to sustain it.

“The state has to bring the dance form back into prominence and ensure revenue for all stakeholders,” said Bhanj Deo. “Today there aren’t many dance colleges which offer courses on the Mayurbhanj Chhau.”

Earning a small income from the dance is one incentive.

“Some of the dancers perform for our guests and earn,” said Bhanj Deo.

Perhaps because of the lure of performance in the palace, young people are showing interest in learning the dance.

Traditionally only men took to the stage, but even that is changing with women being welcomed into the dance troupe.

Dezi Behera used to study classical dance Odissi. But when there was a summer workshop on Chhau, she decided to join.

Behera, now 22, has been learning Chhau since she was 18. As part of the Project Chhauni unit, she has performed in Kolkata, Nagaland and Nagpur.

Even royal descendant Akshita Bhanj Deo is learning the Chhau dance.

Sadly, being a Chhau dancer does not bring in much money. So, many dancers work in other jobs to make ends meet. While this is understandable, it does mean the art form loses refinement, according to Chhua dancer Prabin Kumar Das, who also works at an e-commerce company.

“If dancers are assured of steady income through alternative means, they would continue practising Chhau all year round. Otherwise, they practice for a few days before a performance and so there’s no refinement,” said Das.

To create alternative livelihoods for Chhau dancers, there have been attempts at alternative skill development, like carpentry and courses at industrial training institutes. But Mukherjee, who not only launched Project Chhauni but is still its executive director, admitted that this has not been pushed very hard.

But as UNESCO included Chhau in its list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010, one hopes the efforts of the government and the royal descendants will preserve this unique heritage.

Deepanwita Gita Niyogi is a Delhi-based journalist.