Assam’s rural theatre: Curtains up or down?

Despite competition from Netflix and YouTube, small theatre troupes in Assam enjoy a loyal patronage. Yet, with acting as their main livelihood, the artists face uncertainty during the pandemic.

Despite competition from Netflix and YouTube, small theatre troupes in Assam enjoy a loyal patronage. Yet, with acting as their main livelihood, the artists face uncertainty during the pandemic.

Bipul Das is the owner and principal coordinator of a “Jatra Dal” based in rural Kamrup district of Assam.

He spends a part of his time acting as a stringer for Assamese newspapers, but his livelihood is from the Jatra Dal. He has been in this business for over 17 years.

The Jatra form of art in Assam originates from a similar art form named “Jatra Pali” in Bengal. Around 1930 the first Jatra was staged in Barpeta by Tithiram Bayan. Later, Brijnath Sarma performed on a much broader scale and popularised this art form.

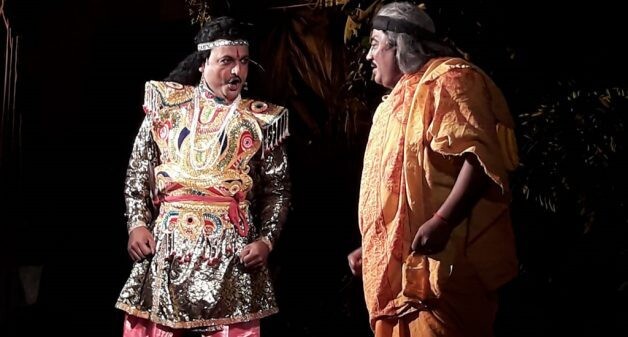

Initially, Jatra was based on mythological and religious themes, were dominated by songs and performed in the centre of a public ground, with viewers surrounding on all sides. While prominence of music remained, later Jatra started being performed on a formal stage with light and sound arrangements.

These Jatra troupes have been experiencing a revival despite the cultural onslaught by social media and streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon Prime.

“You see, when we go to perform, the stage is in an open ground and no one is excluded. The whole village and its neighbouring hamlets come to attend. The show is a big festive occasion as they meet friends and enjoy together. How can all this be replicated on Netflix?” Bipul Das said.

The art form enjoyed rural patronage till the pandemic struck.

A part of rural culture

Das’ dal or troupe has over 30 persons: actors, singers, instrumental artists and others. They generally rehearse new plays – usually each show lasts three hours – during August and September.

From the day of the Biswakarma Puja, occurring usually towards the fourth week of September, they stage these plays at the behest of residents of villages in a region spreading as far as Dhubri in the west and Morigaon in the east.

Their season lasts till the month of Baisakh (May in the following year). Over these eight months, they stage these plays many times and the fees received are used to pay the artists.

“Most of my artists are people who depend on these performances for their livelihoods. During the day, some of them go for hajira (daily unskilled labour work) or they run petty shops or attend to their goat or small plots of land. Come evening, they are available back stage to be painted and performing on stage,” said Das.

“The more powerful competitors are called mobile or roaming theatres. These groups are much larger. They put up tents for the whole troupe near a village, erect the stage and perform. Individual viewers need to pay for seeing the performance,” said Bipul Das.

“The Jatra Dal on the other hand is a smaller troupe. We depend on the hosts for the local arrangements and the availability of the stage for performing. We simply reach the village by 4 or 5 pm, put up our sets on the stage and start performing by 7.30 or 8 pm. By 11 pm we are through and wind up and return,” he said.

The lead actors are contracted for the whole year and are paid a sum up to Rs 80,000 or even Rs 1 lakh. They have to be booked for the whole year and some advance paid. Small-time actors and musicians are paid on a per performance basis and may earn between Rs 400 and Rs 800 per night of show.

There are some 20 such troupes in the southern part of the Kamrup district. The Jatra Dal is a feature to be found especially in lower Assam and the audience too is mostly here. There are over 60 such troupes in Goalpara, Dhubri, Barpeta, Kokarajhar, Rural Kamrup and Nalbari districts.

A vast repertoire

“We do both mythological plays as well as plays with more contemporary social themes. We prepare three or four plays in August-September and perform what the audience wants us to,” Das said.

In his experience villages with more Bengali speaking audience prefer mythological stories translated from original Bengali, with songs set to old Bengali tunes. Even tribal villages opt for these mythological themes. Elsewhere people like social themes

We have also done Hamlet as well as Oedipus Rex in some years, so we are really not confined to Hindu mythology,” he said.

Rural patronage

Village elders from big families consider it a matter of pride to sponsor the shows and some families come together to pay Das and his troupe themselves, as well as get their dinner after the show.

In recent times commercial actors have started paying small amounts for putting up their banners during the show.

The artists sometimes get critical acclaim and their reputations grow, landing roles in television serials. But this is more common among the mobile theatres, where the contacts, visibility and spending power are larger.

Pandemic woes

But COVID-19 hit them hard.

Das said that by the time lockdown was declared in March 2020, about half the season was over. They lost the remaining half and they were also unable to rehearse new plays as gatherings were banned well into that year.

“The three or four months after November 2020 were very nice, we did more shows than the previous years,” he said. The reason was that his was among the few troupes which had readied itself to perform during those months. “But 2021 has been awful since the start of the second wave in March 2021. The restrictions on gathering are still in force and there are no performances.”

Such troupes performing these dramatic shows are a remarkably special aspect of Assamese life. And it is not just an elite art but for all people.

Das, though, regrets that they do not have wider sponsorship.

“While we do have sponsors from the rural elite, it’s difficult to say that people in general are generously supporting us financially or even granting respect to us as artists,” he said.

Sponsorship needed more than platitudes

Does the state help these troupes survive?

“Our Association went to meet the chief minister and the culture minister in Guwahati. They all patted us on the back and said we are doing very good work and they will see what they could do. But nothing has been offered by the state,” he said.

It appears that sporadic support to poor artists has been offered by local political leaders or MLAs, but no help has come from the government.

It is as if the government says: ‘I know you represent a part of my dear culture. Keep it up, keep the culture alive,’ but does not want to offer real help.

Saratchandra Das is the executive director of Grameen Sahara, a non-profit organisation.