Coastal farmers harvest riches with hardy vetiver

Farmers in India’s east coast, which is vulnerable to cyclones and floods, have found commercial success by growing vetiver, a perennial grass also known as khus that has a variety of uses

Farmers in India’s east coast, which is vulnerable to cyclones and floods, have found commercial success by growing vetiver, a perennial grass also known as khus that has a variety of uses

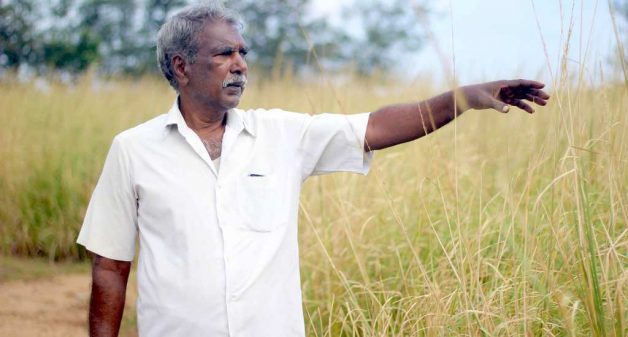

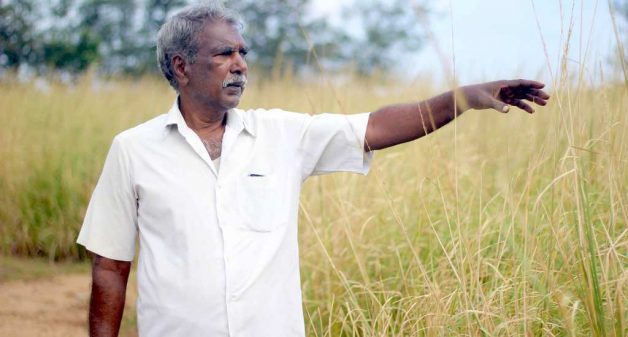

With the backdrop of salty breeze and sound of waves lies Chandrasekar’s farm, just 50m from the Bay of Bengal coast. Chandrasekar (60) of Naramai village in Puducherry has been farming here for more than two decades.

He grew casuarina and coconut trees earlier. “Casuarina trees give us yield every six or seven years and is a common sight in this coastal stretch. But in 2011, when Cyclone Thane struck us, it destroyed the entire plantation. We were left with nothing,” said Chandrasekar.

It was at this juncture that he heard about vetiver or khus (Vetiveria zizanioides), a perennial Indian grass, that could be harvested in about eight months. With nothing to lose, Chandrasekar took to vetiver cultivation, and within a year made a profit of more than Rs 1 lakh per acre.

Many farmers like Chandrasekar living along the east coast have found vetiver not only hardy to withstand salinity and resilient against weather anomalies, but commercially viable as well.

Hardy grass

“Being in a low-lying area, water often gets stagnated in our farm during heavy rains. Vetiver is able to survive the flooding,” Chandrasekar told VillageSquare.in. “Vetiver fares well when the groundwater gets salty at times due to seawater intrusion. Vetiver is the best bet for a coastal land like ours.”

Farmers in neighboring Cuddalore district face a similar situation as the increasing salinity of the coast make it difficult for crops to survive. While the district had a few vetiver farmers, it was only in the last five years that the east coast has taken to vetiver cultivation on a large scale.

Climate-resilient crop

Bhagiyaraj (23), a farmer of Nochikaadu in Cuddalore district, recalled how his vetiver crop survived the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. During that period, his father had cashew and casuarina trees and had planted vetiver only in two acres of their 20-acre farm.

“I remember how everything wilted or was washed away,” Bhagiyaraj told VillageSquare.in. “However, the vetiver grass that had turned black after the tsunami was as good as new within days of being watered with fresh water.”

According to Prasanna Kumar (25), a young farm entrepreneur of Subramaniyapuram, a few years ago, farmers were selling their lands to factories as they could not grow anything. Farmlands were becoming dump yards because of increasing weather anomalies such as storms and floods.

“When they realized that vetiver could be resilient against these climatic conditions and still help them gain profits within a short span, more farmers took to growing it instead of selling their lands and migrating,” Prasanna Kumar told VillageSquare.in.

New markets

Bhagiyaraj’s father increased vetiver cultivation area from 2 acres to 5 acres. “When the perfume industry opened up, demand for vetiver oil made from the roots increased, and I convinced my father to grow vetiver in all 20 acres,” he said. This helped them earn nearly Rs 2 lakh per acre in consecutive harvests.

Generally, farmers here sold vetiver roots to naatu marundhu kadai, stores that sell traditional medicine.Now start-ups like Prassana’s Marudham have opened up the local vetiver market to the booming perfume and handicrafts industries across the country, creating good returns for the farmers.

Livelihood for women

In this coastal district, vetiver has also become a boon for rural women like Poongothai (40), who works in a local self-help group and makes products like garlands, yoga mats, laptop bags, scrubs, etc. with vetiver. In the last five years, Cuddalore has become a hub for vetiver and products made of it.

“I was a homemaker, but last year, women like me from the neighboring villages got together to make and sell vetiver products to the local handicraft industry,” Poongothai told VillageSquare.in. “I have been earning Rs 6,000 per month. The unit is close to our homes, helping us earn extra income for our family.”

Environmental use

Farmer D. Enbarasan (25) of Cuddalore said that vetiver tillers are in demand across the state for environmental purposes. “After severe droughts in the state, there are efforts to revive water bodies across Tamil Nadu. We supply vetiver slips to environmentalists, who plant them around water bodies to strengthen the bunds.,” he said.

“Apart from preventing soil erosion, the thick vetiver roots are used for phytoremediation, a process that removes contaminants from water and soil. This is another use of vetiver that has gained lot of attention recently,” Enbarasan told VillageSquare.in.

Recently, Enbarasan supplied vetiver tillers to a dairy firm for treatment of their effluents. Mention of vetiver in ancient texts like Arthasastra reveal that it has been used to clean wells and water bodies in India since time immemorial.

Oversupply

Senthur Gugan (26), a farmer of Nochikaadu, said that the government too jumped in the vetiver bandwagon and helped by giving free vetiver tillers through local panchayats. With this, area under vetiver cultivation grew from 100 acres to 700 acres in Cuddalore.

With the market taking a downturn this year, the farmers have not been able to sell vetiver at its usual price. “It would be good if the government provides an option to buy from us, as it would be difficult for the private sector to absorb so much produce,” Senthur Gugan told VillageSqaure.in.

Traders said that with the imported vetiver crops costing less than local crops, Indian companies are importing despite availability of sufficient and better quality produce. “Maybe, it would help if we have a fixed selling price for farmers,” said Chandrasekar.

While coastal farmers have learnt to live around the various challenges that nature throws at them, the market instability is still a deterrent to new entrants. As for old timers like Chandrasekar, their faith remains unperturbed. “Next year will be better.”

Catherine Gilon is a journalist based at Chennai. Views are personal.