Deaf-mute Kashmiri woodcarver’s work leaves world speechless

Woodcarver Muhammad Yusuf Muran of Srinagar is known to be the man with golden fingers. His Midas touch on his family’s 200-year-old craft amplifies Kashmir’s handicraft heritage.

Woodcarver Muhammad Yusuf Muran of Srinagar is known to be the man with golden fingers. His Midas touch on his family’s 200-year-old craft amplifies Kashmir’s handicraft heritage.

The dull, rhythmic “thuck” of hammer meeting chisel on wood captures the sound of silence at Muhammad Yusuf Muran’s workshop in the quiet neighbourhood of Narwara in downtown Srinagar.

The 57-year-old carves out images hidden in blocks and hunks of dead walnut wood – one chip, one peeling at a time.

The pieces of art and his warm, infectious smile tell much more about his woodcarving skills and the Kashmiri family’s 200-year-old heirloom trade than anyone can put in words.

He shows with free admission his art and love of wood. Without a word. He can’t hear or speak.

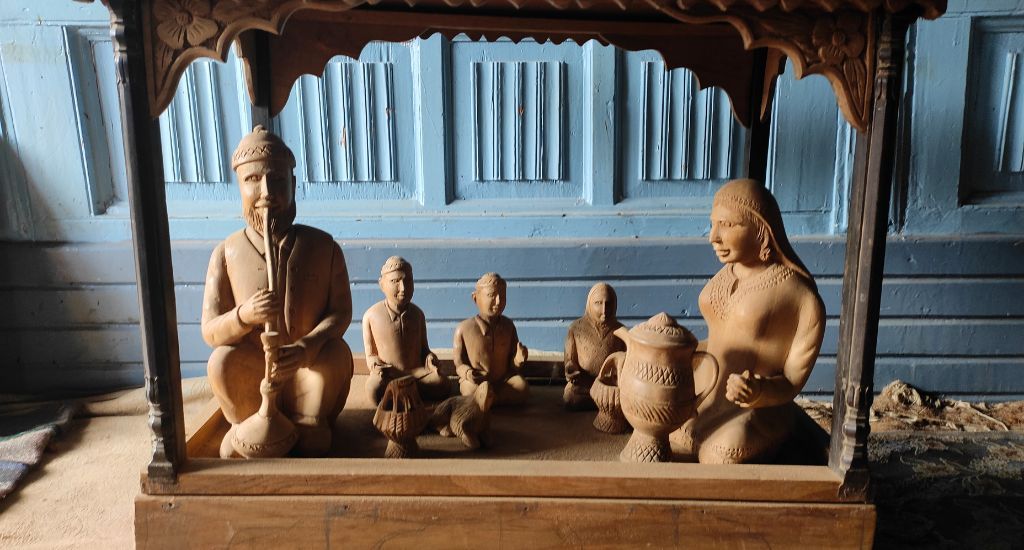

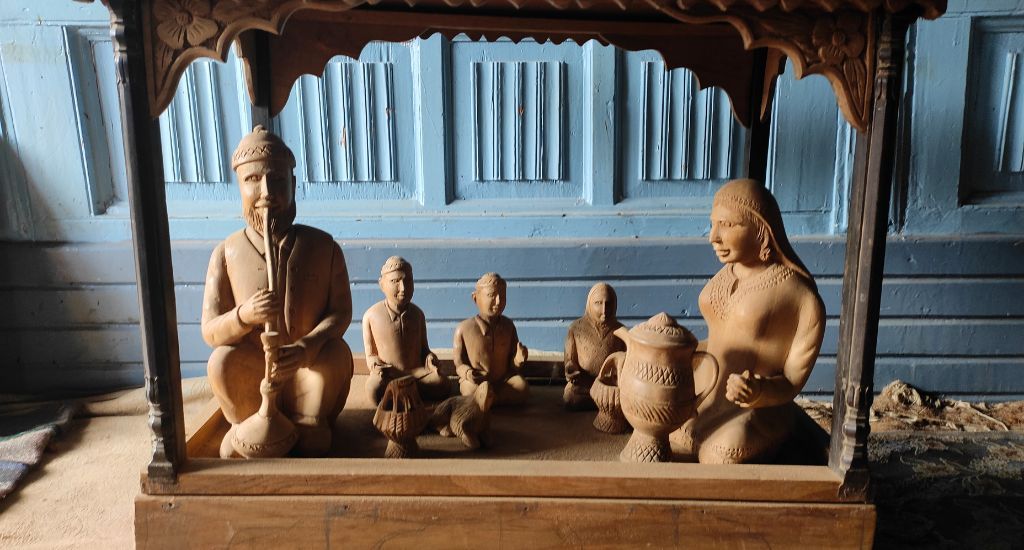

The deaf-mute woodcarver’s repertoire includes relief carvings, chip carvings, animals and birds such as a herd of elephants trotting on a field or an eagle spreading its wings, and characters like an elderly Kashmiri man puffing at a traditional hukah, a family enjoying tea from a samovar in rural setting.

There’s a detailed sculptured Sir George too, straddling a horse and fighting a dragon, or a replica of Srinagar’s famous Jamia Masjid.

I have seen many masterpieces by artists, but this man is in a class of his own. Perfect

Kashmir is still widely viewed more as a source of fine art for foreign collectors rather than a market in itself. That may be slowly changing.

The craft goes back millennia and Muran’s newfound fame is bringing the bounty through direct and online sales of his products.

His artwork travels far and wide, bringing him recognition and accolades. Tour guides even include his small workshop tucked away in one of many lanes of Narwara in their packages.

Passers-by stop to admire his work and take photos with their phones.

“I have seen many masterpieces by artists, but this man is in a class of his own. Perfect,” said Adil Naqash, interior designer from Nishat, a township on the eastern outskirts of Srinagar. “He has golden fingers.”

Muran has been woodworking since boyhood, helping with his father’s projects.

“Then his elder brother Abdul Ahad Muran, who died a few years ago, taught him old-timey woodworking” said Arsalan Yousuf, the woodcarver’s younger son.

Arsalan is modest in his praise of his father. “He is like any other artist, but his popularity stems from his dedication to the craft and hard work. He works 9-to-6, six days a week, except Fridays. He goes to the market in the morning to buy wood and spends his evening visiting places of worship and praying.”

He’s likely the only person one would expect to find woodcarving on a Sunday. Dot at 9am, he walks down the stairs and slips into the backyard where a pile of wood awaits him. His trained eyes locate what he needs and he lumbers into his workshop with a round wood block.

From start to finish, it takes him about an hour or two to carve a small bird by hand, then sand and seal it.

Carving is therapeutic, and time elapses without thinking much about it. Many carvers will say woodworking leads to a state of flow. They can carve for hours and not think about too much else. That’s particularly true for Muran.

There is also something special about making a physical object with the hands, especially if the artistic medium comes from nature.

Muran uses walnut, not an easy wood to work on. It is a straight-grained, moderately heavy hardwood, though it can sometimes have waves or curls that enhance the character of a piece.

Walnut is typically clear-coated or oiled to bring out its natural colour, which can vary widely, even across the same board, from yellow sapwood to deep chocolate brown. The wood dries slowly, with little shrinkage.

It’s hard to find quality walnut or deodar wood. Nazir Ahmad, a dealer in Srinagar, said a government ban on cutting walnut trees has pushed up prices. Muran’s son Arsalan chipped in: “We have to often pay a premium and that cuts into our profit.”

Like the wood Muran labours on, there’s a dearth of interest among youngsters in the labour-intensive trade that demands loads of patience and years to master.

The government is promoting Kashmir’s handicraft industry with heritage walks and safaris, and workshops to attract the youth to the heritage crafts—trying to get them hooked first as a hobby.

“We have artisan-friendly schemes to encourage the youth to take up art as a source of livelihood,” said Mehmood Ahmad Shah, an official with the Jammu and Kashmir handloom and handicrafts department, referring to a push to preserve skills of masters like Muran.

The lead image at the top shows Muhammad Yusuf Muran’s creates wonders with wood such as this one, a Kashmiri family enjoying tea from a samovar (Photo by Nasir Yousufi)

Nasir Yousufi is a journalist based at Srinagar.