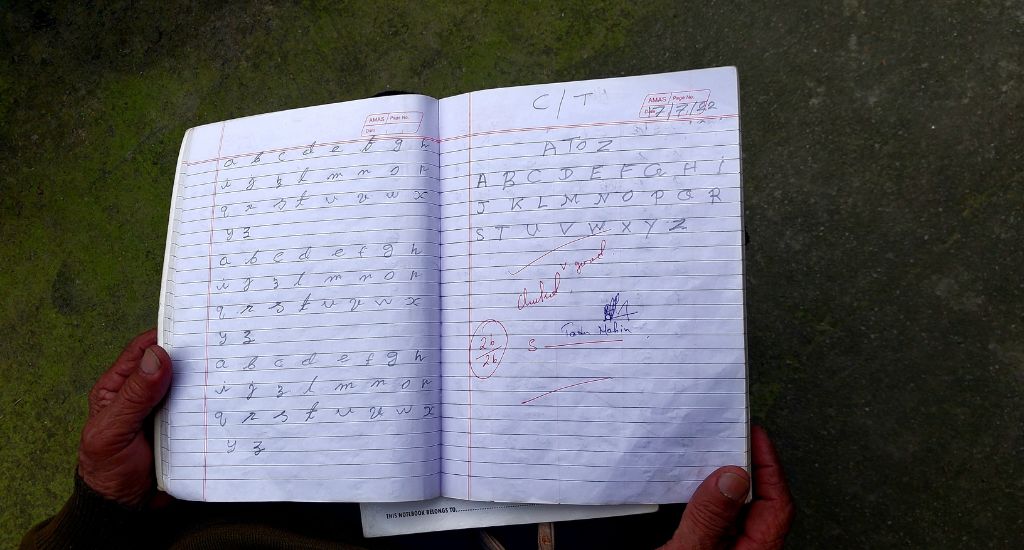

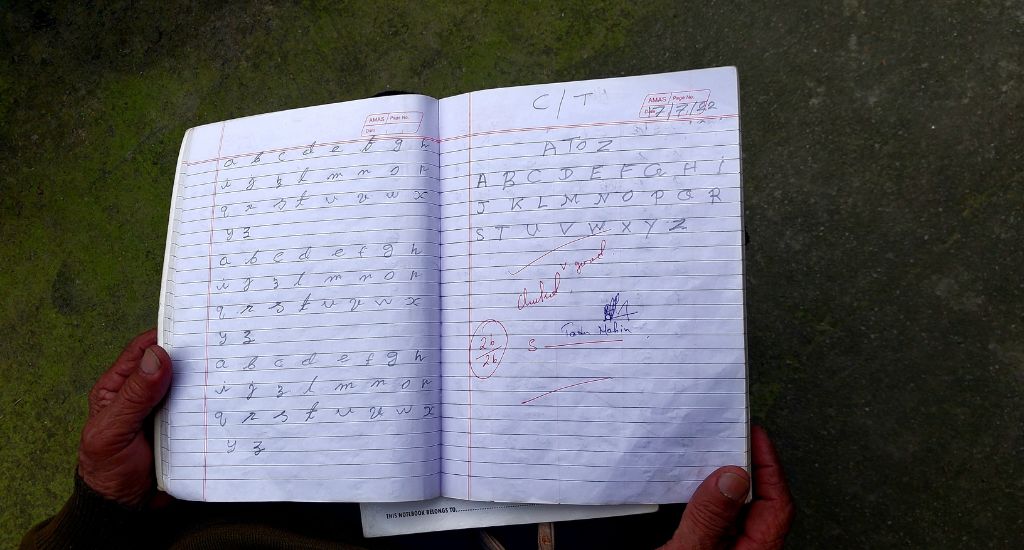

Elderly Apatani village heads learn English alphabets

17 village headmen and headwomen, illiterate and elderly, attend adult education to learn English for document signing, to prevent misuse of their thumb impressions.

17 village headmen and headwomen, illiterate and elderly, attend adult education to learn English for document signing, to prevent misuse of their thumb impressions.

It’s better late than never for village chieftain Tillghk Morth, an Apatani tribesman from Ziro valley of Arunachal Pradesh, the horseshoe-shaped mountainous state in the Northeast, bordering China and Myanmar.

Tillghk is in his seventies and worldly-wise. But he was never a man of letters until he began learning the ABCs of English in the summer of 2022. He can now sign documents and read signage, or at least spell out letters and figure out what’s written – an instruction or the name of a place.

No more “taachingma” – meaning “I don’t understand” in Apatani – for him.

He is a diligent student and attentive in his class of 17 illiterate village headmen and headwomen – called gaonburha and gaonburhi, respectively. Classes are held every Sunday at the Government Middle School in Bamin Machi Dukru village, about 3km from the township of Old Ziro.

When the weekend classes first started, 27 enthusiastic elders with wrinkled and freckled faces enrolled, but 10 of them dropped out one by one, in phases.

“None of them had gone to school,” said their 20-something teacher Hano Usha, who’s teaching them voluntarily. “They forgot things again and again when they started. Now they are learning and all of them are able to write capital letters.”

Tillghk comes to class wearing his signature red half-jacket, a relic from the colonial past when Arunachal was known as North East Frontier Agency. Each gaonburha was given a bright red, woollen coat so that the British administrators could identify them. The dress code continued, although the sleeves were dropped for comfort in the summer months.

Tillghk has been a village headman for decades and his coat has become inseparable. As the teacher dictates the spelling of “Apple”, and the class repeats after her, Tillghk’s deep baritone from the front row can be heard afar.

“I used to put the thappa (thumb impression) when people came to me for my sign on official papers. Now, I sign,” he said with pride.

Ziro, also known as the land of the Apatani, is a saucer-shaped valley at an altitude of 2,400 metre, with pine-clad mountains bounding it from all sides. Old Ziro and Hapoli are two small towns in the valley, which are ringed by villages along the foothills. Hapoli is the capital of Lower Subansiri district.

A community of about 44,000 people, the Apatani are among 26 major tribes of Arunachal, a sparsely populated tribal state.

The Apatani are known for their wet paddy cultivation and the rice fields stand at the heart of the valley and the tribe’s identity and culture. They are also recognised for their progressive attitude and a high literacy rate of more than 75%.

But Tillghk and his peers are from the yesteryear generation that either missed out on formal education because their parents didn’t allow them to go to school, or they dropped out.

“When we were young, we only went hunting. I have never been to school,” said Tadu Yarang, the gaonburha of Mudang Tage village, who too is taking English lessons. “I got very good marks in the ABCD (capital alphabet) test,” the 70-year-old said.

Neighbour Tage Yassung, 53, is the gaonburhi of Mudang Tage. She has never been to school, but can now read and write. “Our teachers are very good. They teach us like children,” she said, laughing. “They punish us too if we fail to do our homework.”

Teacher Hano is proud of her students. All of them passed a test held in April.

“They got a little confused with the small letters. But everyone can sign now. It’s really fun,” she said.

The adult education programme for the village elders is a brainchild of social activist Yachang Tacho, who also organised a pageant for gaonburhis and gaonburhas in 2019.

It was a challenging task as none had ever used a pen before

Tage Yassung and Tillghk Morth were among the winners from a field of 20 contestants who won everyone’s hearts as they sashayed on the stage in traditional Apatani attire.

“Gaonburhas are essential village institutions. No work is carried out without their involvement. They play a vital role in identifying documents such as land possession certificates, permanent residence certificates, and ST certificates before forwarding them to higher authorities,” said Yachang.

Since most village heads were illiterate and thumb-signed documents without knowing the contents, Yachang felt it was important to educate them because any unscrupulous person can take advantage of their ignorance and misuse the thumb impression. And so, he initiated the basic English programme for three villages – Dutta, Mudang Tage and Bamin Michi.

“It was a challenging task as none had ever used a pen before,” he said.

To motivate them, Yachang held a drawing competition for the village heads last year. That’s another first for them: holding crayons and pencils, and drawing on paper.

“They drew random objects, and we printed their artwork to display at the annual Dree festival. The competition was a hit and ignited their curiosity to learn,” Yachang said.

The lead image at the top shows Tadu Yarang, the gaonburha of Mudang Tage village, showing his notebook. (Photo by Ashwini Kuamar Shukla)

Ashwini Kumar Shukla is a journalist based in Jharkhand. He is an alumnus of the Indian Institute of Mass Communication and writes about rural India, gender, society and culture.