Surprising findings on India’s food habits

A new study by the Development Intelligence Unit (DIU) sheds light on rural India’s eating habits, debunking several myths, like richer people eat a more diverse diet than the poor.

A new study by the Development Intelligence Unit (DIU) sheds light on rural India’s eating habits, debunking several myths, like richer people eat a more diverse diet than the poor.

In a sure sign of development, India has shifted from worrying about food security to worrying about nutrition security – ensuring its people get a richer, more varied diet.

Simply put, a more diverse diet means more nutrition, more nutrition means healthier people, a healthier population helps create a healthier economy, which means a stronger, more prospering India.

But this is not happening.

In an attempt to grasp India’s various dietary patterns – including its diversity and accessibility to a wide range of food – the newly formed Development Intelligence Unit (DIU) conducted a pan-India survey, How Rural India Eats – Food Plate Mapping Study.

Typically, gathering such data has not happened frequently enough to gauge the true nature of how people eat. So this will be the first in a series of surveys that will delve deeper into diet deficiencies and the policies that try to help people eat better.

DIU is a joint initiative between the Transform Rural India Foundation (TRIF) and the social research firm Sambodhi.

“Food is the only solution against malnutrition. In order to design interventions, it’s essential to study what people are eating. This unique study brings reflection on how nutritional deficiencies are met at the family level, women’s dietary intakes and cultural norms that are required to make region specific programmes,” said Shyamal Santra, public health and nutrition lead at Transform Rural India Foundation.

There is a common misconception that poor people have poor diets and rich people have diverse, healthy diets. While evidence suggests that diets are influenced by affordability, DIU’s initial survey suggests that there are other dominant factors too that are related to diets, like, habits and culture.

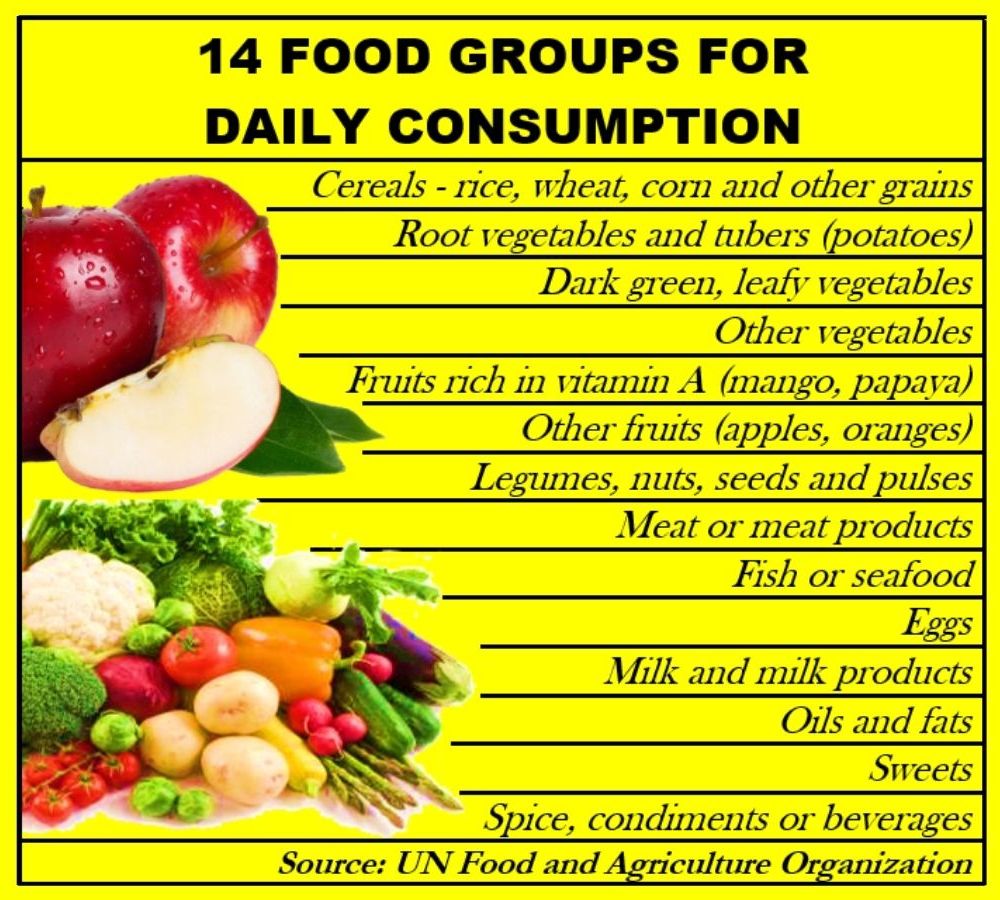

Though one usually thinks about the five major food groups, at a micro level food can be divided into 14 categories, according to the United Nation Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), a mix of which is vital to maintain a well balanced, nutritious diet.

Surprisingly, the survey found the difference in diet diversity between the groups with the highest and lowest standard of living was not much. For instance, in the south zone of rural India, the difference in diet diversity scores of people between the highest and lowest standard of living is only 0.6 (out of 8).

This means that many factors play a role in diet diversity – not just whether a person is well off or not.

While the food plate composition showed a similarity across the country, there were variations in specific food items across regions. This means dietary diversity is likely to be caused by many different reasons, like habit and cultural practices, not just wealth and affordability.

Not surprisingly, cereals are the primary food items across all the regions, followed by oils and fat as well as other non-leafy vegetables.

Eggs, fish and seafood are amongst the least consumed food items, showing India still has low animal-based, protein-rich diets. The consumption ranges from 2% to 41%%, the lowest being the west and north and the highest being the northeast regions of Assam, Nagaland and Tripura.

This is most likely due to multiple reasons from affordability and accessibility issues to cultural preferences.

Given the northeast’s preference for an animal-rich diet that is high in protein, as well as their love of dried fish, it appears to have the most diverse diet in India. It also has the highest proportion of individuals consuming Vitamin A and iron-rich food.

“The idea of the survey is to empower policymakers and development practitioners with timely insights from rural households through recurring rounds of surveys. This will enable seasonality, trends to be mapped and, with time, we will be able to forecast patterns,” said Shubham Gupta, Senior Manager, Sambodhi.

The study also analysed diet diversity within each region. This will be tremendously helpful to state governments and NGOs that want to develop region-specific programmes that ensure nutritional security.

For example, in the case of the western region the average individual diet diversity score (IDDS) is 3.32 – but there was a vast difference between the mean lowest (at 1.96) and the mean highest (at 4.4). That is a difference of 2.48.

This points towards the vast difference in the nutritional intake of individuals in this region and a possible situation of worse nutritional security there. It is a region with extremely low consumption of not only animal-based food but also fruits rich in Vitamin A and leafy, green vegetables.

Just where India gets its food is also enlightening. Where do rural Indians go grocery shopping when there are no extravagant supermarkets?

The DIU survey showed that most of the cereal rural Indians consume is from their family farms. The only exception to this was in northeast and southern villages which are dependent on public distribution system (PDS) shops.

Everywhere else in India PDS shops are accessed less than other stores – preferring local daily markets followed by weekly markets.

The DIU How Rural India Eats – Food Plate Mapping Study series is focusing on the consumption side, aiming to understand food access and affordability and perhaps, will delve into the production side later in the series.

This first study covered 7,332 rural households across 16 states, grouped under six geographic regional zones. These were conducted via sambodhipanels tech platform over a period of one month.

Using the framework of the UN’s FAO, the survey captured people’s food consumption over a 24-hour period and grouped the food items into 14 categories.

Respondents were then scored out of 14 depending on whether they consumed foods under these categories, known as their individual diet diversity score (IDDS).

In order to gauge a respondent’s wealth status, DIU asked questions relating to people’s ownership of assets, like a TV, car or bicycle.

The next study in the series is likely to be released in October of this year.

The lead image shows a roadside vegetable stall in Meghalaya (Photo by Kankana Trivedi)

Kankana Trivedi is the manager at Development Intelligence Unit (DIU) and interested in environment and social justice issues.