Weavers keep Bastar’s pata saree tradition alive

Artisans are hopeful traditional handloom weaving will get a much-needed boost in Bastar, Chhattisgarh - home of the pata saree - as the government plans to start a weaving hub.

Artisans are hopeful traditional handloom weaving will get a much-needed boost in Bastar, Chhattisgarh - home of the pata saree - as the government plans to start a weaving hub.

Every state or region in India has age-old varieties of sarees to call its own.

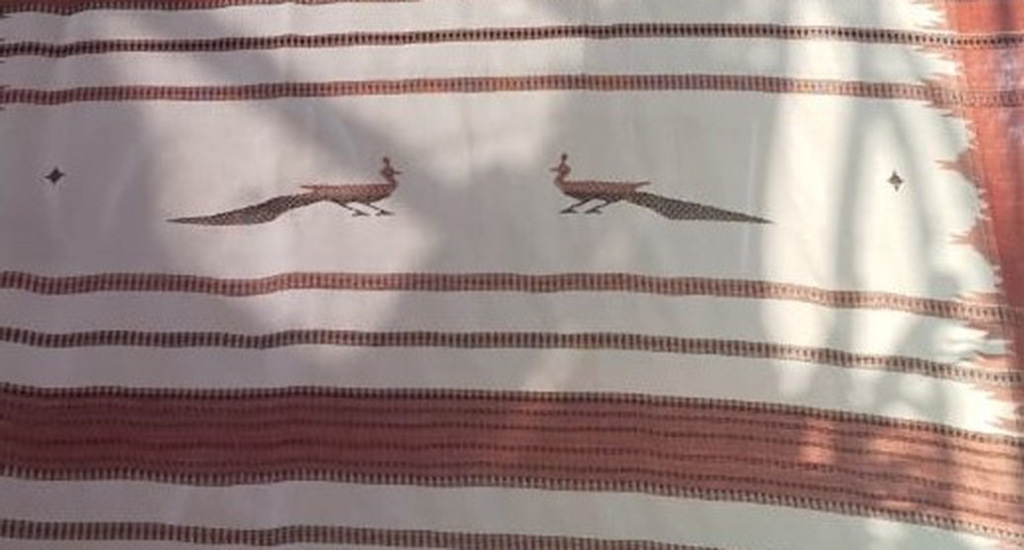

Bastar has its very own pata saree, with its maroon or burgundy border and intricate, nature-inspired motifs on a creamy white background.

It is the attire that the women of the Dhurwa tribe in the Bastar region wear.

Koypal village was once the hub for weaving pata sarees.

But with the availability of mass-produced cheaper sarees, the number of weavers has dwindled.

Hope is on the horizon, though, as the government is taking steps to revive the traditional craft.

In a moderately-sized room with blue walls, weaver Sonadhar Das, swings his legs down into the pit of his loom.

He is one of the few weavers in Koypal continuing the tradition of weaving pata sarees.

Close to Das’ loom is a makeshift workshop that used to accommodate many weavers, but is not in use now.

“Talented weavers turn to MGNREGA work since that brings assured money,” said Das’ son Shiv, referring to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme that assures 100 days of work to rural people in a year.

“Because it takes time to make sarees. Income depends on the orders we get. Sometimes, payment is delayed,” Shiv added.

But it is a rich tradition that Shiv – a graduate who is yet to master the craft – wants to keep alive. (ALSO READ: Traditional handloom weaves a comeback in Kachchh)

As his mother drew the fibres to make yarn, by rotating the dala (a simple charkha-like mechanism), Shiv said that wooden looms were on the decline.

Only six people in Koypal use wooden looms, though Sonadhar Das had trained about 20.

The wooden loom – made from a tall tree locally called karsari – gives the sarees a neat finish. It is straight and does not bend, an essential quality needed for wooden looms.

Though the Dases can upgrade their family loom, they are against it. Sonadhar Das’ father had made it using wood from the forest. Besides this legacy, the quality of the saree it produces is another reason.

“Most sarees these days feel like bedsheets and lack quality,” Das told Village Square.

Modern looms create pressure on the sarees but wooden ones are light.

Bamboo is not strong and may break due to the constant tug and pull of weaving.

“A rope tied to the wooden loom keeps the starched, half-finished saree straight while weaving,” Shiv said.

All these factors reflect in the quality of the material, producing a richer saree. (ALSO READ: Adapting to market needs, weavers find financial success)

Another cultural reason is that Bastar’s deities are placed on iron chairs during tribal festivals. So, people here do not wear clothes made in iron looms.

Nature is at the centre of pata sarees, be it the border or the tree used to make the loom.

The pata sarees have motifs of peacocks, tigers, deer, turtles and more.

The dyes are obtained from the roots and bark of the Indian aal tree, also called jara jhar. Black and green hues are rarely used as there are no natural dyes for these colours around the locality.

Getting the natural dyes takes time. But that is not the only tedious aspect of producing these sarees.

One saree needs threads worth Rs 2,500. And these threads are not close to hand.

The coloured yarns are sourced from the Nabarangpur and Sambalpur districts of Odisha. The white thread is sometimes obtained from Jagdalpur, Bastar district’s headquarters, which is 18 km away.

Weaving a pata saree may take seven days or more to finish, depending on the intricacy of the designs.

At this rate Das’ family makes up to five sarees a month.

They hope to sell them at the market for Rs 7,000 to 9,000. It is little wonder that the weavers often cannot find buyers.

But the government wants to sustain the art and is stepping in to help the weavers. It has budgeted Rs 22 lakh for a community weaving centre in Koypal.

“We’re in the process of identifying a land,” said Astha Rajput, sub-divisional magistrate of Bastar’s Tokapal block.

Gobardhan Panika, an Odisha-based weaver and Padma Shri recipient, rued that young weavers were yet to learn the intricate motifs.

The government hopes to set that right.

“We will train youth and streamline the weaving process,” said Rajkumar Dewangan, programme manager of National Rural Livelihood Mission for the Bastar district. “The thread dyeing will also happen in Bastar to reduce the cost.”

Shiv is happy with the recent interest urban designers are taking in pata sarees. But he is wary they might break from tradition.

“Two women designers came from Mumbai to learn from us. Though we welcome such interest, modern designers will invariably change the loom,” he said. “Unfamiliar with pit looms set on mud floors, they might want to avoid dust collecting on the sarees while weaving.”

Das hopes that the newly-formed Bastar Kala Gudi Producer Company – a cooperative which makes and promotes artisans’ products – will help their sarees find a steady market.

And so with a renewed sense of optimism surging through his fingers, Das continues his work on a saree someone recently ordered for an upcoming festival

Deepanwita Gita Niyogi is a Delhi-based journalist.