Profiting from propagating native seeds

Hearing of a likely seed famine, marginal farmer Sudam Sahu of Odisha started conserving native seeds and now champions organic farming with those seeds.

Hearing of a likely seed famine, marginal farmer Sudam Sahu of Odisha started conserving native seeds and now champions organic farming with those seeds.

After a crop loss for two consecutive years, Manglu Sahu is happy with a harvest of 44 quintal of paddy from two acres.

The marginal farmer of Odisha’s Bargarh district praises local ‘seed saviour’, Sudam Sahu, for coming to his rescue.

“I was already deep in debt – I had no money to buy seeds for the next season. But Sudam Sahu came to my rescue. He gave me seeds of talmuli – an indigenous high-yielding variety – free of cost,” Manglu Sahu said with gratitude.

Like Manglu Sahu there are hundreds of farmers in the same district who look for Sudam Sahu’s guidance and help.

But who is this seed saviour?

Hailing from Kantapali village, Sudam Sahu is also a marginal farmer, but one who is into native seed conservation. Sahu not only conserves indigenous seeds but also encourages others to cultivate crops with those seeds.

Hailing from a farming family, Sudam used to help his grandfather work his 2-acre land – one acre which was mortgaged to pay for the medical treatment of his father.

When his father’s health deteriorated, Sudam dropped out of his final year of school to work on the farm.

“I learnt farming from my grandfather. He practised organic farming with two native varieties,” recalled Sudam Sahu.

“In 1999 I heard a speech by Kishan Patnaik, an activist and former member of parliament from Sambalpur. He explained how modern technology was upending indigenous farming and said that one day there would be a seed crisis – he called it ‘the seed famine.’”

Motivated by Patnaik’s speech, Sahu’s aim became conservation of native seeds. He decided to preserve native seeds with the help of his grandfather – a fount of traditional knowledge.

He was so dedicated to this new passion, Sahu even declined a government job offer so he could continue farming and conserve seeds.

To learn more about quality seed production he attended trainings organised by a group of non-profit organisations working among farmers.

Initially he visited villages and gave one or two varieties to interested farmers. They cultivated and then passed on the seeds to another farmer and then another and on it went.

Realising the slow progress, and wanting to ensure sustained organic seed conservation, he attended training programs at the Gandhi Ashram in Wardha, Maharashtra as well as a session in the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) South Asia Regional Centre.

Starting with his grandfather’s two paddy varieties, Sahu slowly collected more seeds.

Whenever he visited places, he collected indigenous seeds.

“About 40% of the varieties I have is what I collected from farmers. About 25 varieties are through exchange,” he said.

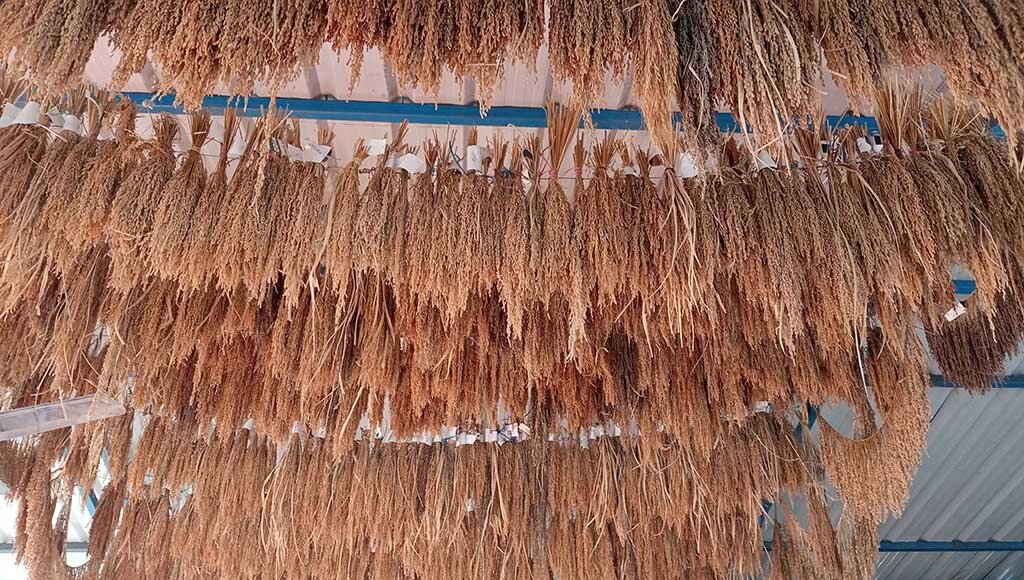

Now he has 1,100 varieties of seeds, including about 1,000 varieties of paddy, some varieties of vegetables, greens, pulses and oil seeds.

In addition, from the IRRI headquarters in the Philippines he sourced 34 paddy varieties which are rich in calcium, zinc, iron, protein and antioxidants and even a few with anti-carcinogenic properties.

He has categorised the paddy seeds as black rice, brown rice, medicinal variety rice, high yielding variety and fine rice.

Through cross-germination, Sahu has created six new varieties of paddy which are believed to have medicinal value, be drought tolerant and provide better yield.

“My seed bank serves two purposes. It provides a wide choice for the farmers and it helps preserve the centuries-old indigenous seeds,” said Sahu. (Also read: Villagers conserve native seeds)

While half of Sahu’s 5-acre land is dedicated to growing crops for his family, one acre is set aside for producing crops so that the seeds can be conserved. In the remaining area he cultivates a maximum of six native varieties that are in demand – on a rotation basis annually.

In his native seed conservation work, Sahu follows traditional methods and stores the seeds in earthen pots.

He lines each pot with cow dung and turmeric paste, dries it in the sun and then keeps the seeds in the pot. He covers the seeds with neem leaves to repel insects.

His wife, Shantilata, helps him in the time-consuming process of preservation and labelling.

From time-to-time he checks the seeds to see that they have not spoiled.

Sahu is passionate that organic farming could help farmers create a more sustainable living that would protect them from unforeseen disasters that destroy crops, livelihoods and lives.

According to a government report, 227 farm suicides were reported in Odisha between 2013 and 2018, most of them from Bargarh – Sahu’s home district. The reasons were crop loss due to untimely rains, pest attack and the burden of debt.

“These farmer suicides deeply upset me. So to help prevent them, I train farmers in organic and sustainable farming,” Sahu said. “Every year I conduct more than 100 training sessions.”

To help farmers and to propagate native seeds, he founded Desi Bihan Surakhya Samiti, with more than 1,200 farmer associates. About 250 of them grow 22 of the native varieties successfully. Since the seeds are in demand, they book the seeds with Sahu in advance.

Sahu encourages farmers in his region to grow the highly nutritious black rice of which he has 14 varieties.

This rice is popular and many of the local farmers, like Birendra Pradhan, are receiving good income from the crop.

“All credit goes to Sudam Sahu. He motivated me to grow black rice,” he said.

While a farmer normally gets Rs 1,800 per quintal, Sahu and his protegees get Rs 4,000 for their organic paddy.

“Farmers can make a profit. But their income will double only if they move to organic farming,” Sahu maintains. “My dream is to see debt-free, self-reliant farmers producing pesticide-free food.”

Sarada Lahangir is a Bhubaneswar-based journalist, who writes about development, conflict, gender, health and education.