Weaving a way out of destitution

Weaving indigenous handloom clothes offers destitute women and those who have been trafficked a safe and stable livelihood in the hills of Darjeeling.

Weaving indigenous handloom clothes offers destitute women and those who have been trafficked a safe and stable livelihood in the hills of Darjeeling.

Full of rosy dreams about marriage and family, Megha Thapa eloped with a young man her family did not approve of.

From Kalimpong her ‘fiancé’ took her to Pune on the pretext of a job.

But sold her to a brothel instead.

Thapa was subjected to intense mental and physical torture for the next four years until she was rescued in 2012.

Soon after she was rescued and the legal formalities were complete, Thapa returned to West Bengal in hopes of starting a new life. Her wish was fulfilled when an organisation working for women’s empowerment offered her a livelihood making indigenous handloom clothes.

The Hills Social Welfare Society (HSWS) is a lifeline for local women subjected to sexual exploitation.

HSWS tries to popularise handloom clothes indigenous to the Darjeeling hills thereby giving the women a market for their handloom work.

“We started training women in this alternative livelihood in 2006 to stop the rising number of women migrating to other states to find a livelihood and also reduce to reduce trafficking,” Shova Chhetri, secretary of HSWS, told Village Square.

They have trained over 3,000 women so far and are training around 600 women this year.

HSWS trains women in making traditional clothes and accessories like mufflers and shawls. It also teaches them to make and market pickles that are popular in the hills.

“Very few women joined initially as it took time for us to convince them to get livelihood training. We had to stop the training for two years because of the pandemic,” said Shova Chhetri.

Thapa makes indigenous handloom clothes like chaubandi choli (a traditional blouse) and gunui cholo (a long skirt) worn by women.

Trafficking is rampant here. Even rescued girls fall back in the web due to utter poverty and lack of livelihood opportunities.

Making these clothes helps Thapa earn around Rs 6,000 per month.

“The income is negligible compared to the money I made in that ‘business’. But it has given me a chance to lead a respectable life,” Thapa told Village Square.

Pasang Doma Lama, a single woman, makes dumdem – an ankle length long skirt worn by the local women.

She earns around Rs 5,000 per month making these traditional clothes and accessories to go along with them.

“I work for six hours and make traditional items that are in demand in Kolkata and other states. The income is enough to run my life and manage my medical expenses,” she said.

Enthused by the livelihood opportunities, many other women are also eager to learn how to make handloom clothes.

“I lost my husband two years ago. I’m also a cancer patient. Still, I am thinking of joining the training so that I can earn by working from home,” said Mala Chhetri.

Women who were moving away from their traditional attire now show a keen interest in wearing them again.

“Earlier, we couldn’t get our traditional handloom clothes easily though we wanted to wear them. But now they’re available and we wear them in social gatherings,” said Ritika Chhetri, a homemaker.

“I must say we get a lot of attention from the guests of other states because of our traditional clothes,” she happily added.

West Bengal has the dubious distinction of recording a high number of human trafficking cases. Poverty and lack of livelihood opportunities in the hills serve as a fertile ground for traffickers to lure young women.

According to National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data, 357 cases of human trafficking were recorded in West Bengal in 2017. This dipped to 172 in 2019.

But activists say that the government figures hardly represent the ground reality as most cases go unreported.

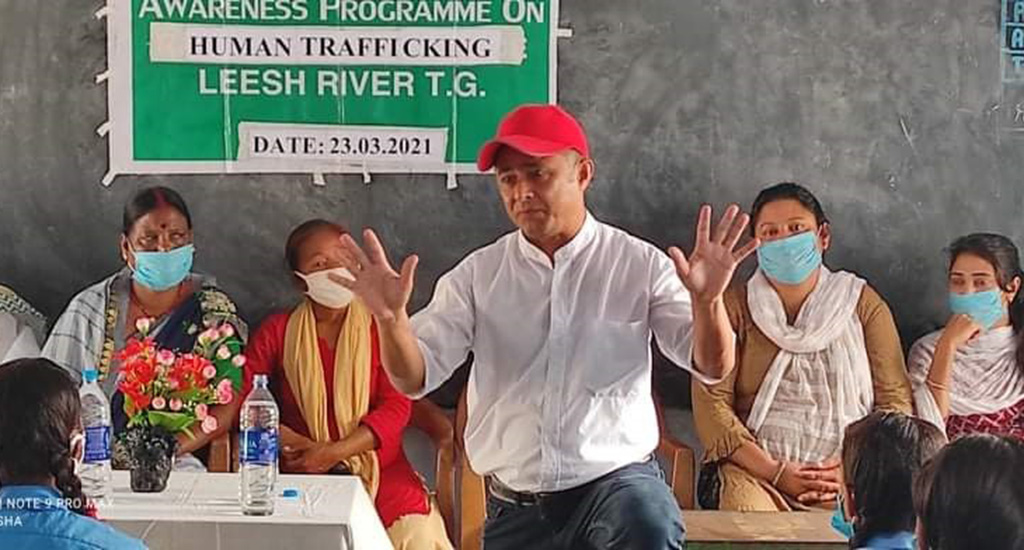

“The numbers don’t give a clear picture. Many cases go unreported. Some are registered as missing persons in government records and forgotten,” said Raju Nepali, a well-known campaigner against human trafficking .

Bengal’s northern districts serve as the gateway to the north-eastern states and also Nepal, according to Nepali.

“Trafficking is rampant here. Even rescued girls fall back in the web due to utter poverty and lack of livelihood opportunities,” Nepali told Village Square.

Most of the woman are sent to Kolkata or other states, especially Maharashtra and Delhi, he added.

Some like Ranjana Gogai – who had been trafficked to Mumbai and was rescued two years later in 2020 – finds a social stigma in taking up jobs.

“Society looks down upon us with disdain. They don’t realise we do this obnoxious work to feed our families and provide them proper shelter,” she said.

Shova Chhetri admits that it is very difficult to stop trafficking completely.

“Women often fall in the trap and get trafficked with the hope of earning quick money. It can be minimised with our efforts. But it’s difficult to stop unless women are economically self-sufficient.”

*Some names have been changed to protect privacy.

The lead photo at the top of this page shows threads used in handloom (Photo by Divyanshi Verma,Unsplash).

Gurvinder Singh is a journalist based in Kolkata.