Palghar’s tribal farmers sow and sell as a collective to reap benefits

Collective farming is not only helping farmers sell their produce far and wide but has also arrested migration and increased the well-being of farmer families

Collective farming is not only helping farmers sell their produce far and wide but has also arrested migration and increased the well-being of farmer families

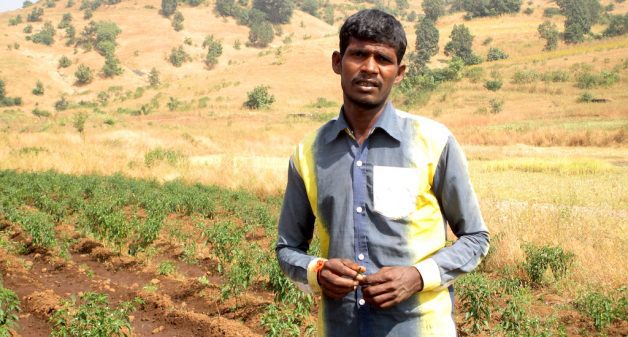

Not long ago, Diwali, the festival of lights, used to bring gloom to the family of Bhaskar Bhau Somamalik, a farmer from Khoch village in Mokhada taluka (administrative block) of Palghar. “Every year, post Diwali, I used to migrate along with my wife and two small children to Nashik or Mumbai to work as a daily wager,” Somamalik reminisced the hard times faced by his family.

Monthly rental for one small room in city slum was Rs 2,000, along with an upfront deposit of Rs 10,000. Since he had no money, Somamalik’s family would squat on the footpath, next to mosquito-infested waste heaps and often fall sick. “By the time we returned to our village for Holi (in March), I would have already spent all my earnings on doctor fees and medication. Migration was our only means of survival,” he said.

That was some six years ago when Somamalik and his fellow farmers from Khoch, mostly belonging to the Thakar scheduled tribe, were facing abject poverty. During the kharif (monsoon) season, they practiced subsistence farming of paddy and finger millet (ragi, locally known as nachani) for self-consumption. In the rabi (winter crop) season, they were forced to migrate to cities for lack of irrigation facilities in their village.

Collective farming

In 2010, Aroehan, a Mokhada-based NGO, approached the tribal farmers of Khoch to train them in growing seasonal vegetables in the rabi season. Since the farmers were extremely poor and owned very little or no land, collective farming was adopted.

To begin with, a group of 10 farmers from Khoch was trained in vegetable farming. Thirty-five year-old Somamalik was one of them. In the rabi season of that year, he sowed okra on 1.5 acre land and earned Rs 50,000; his life’s first ever earning from the rabi crop.

There has been no looking back since then. Somamalik has stopped migrating to cities to clean the gutters, or work as a construction labourer. He spends both the kharif and rabi seasons in Khoch itself. However, his produce gets sold in the international market. “I now grow vegetables such as French beans, okra and chilli. Last year, I exported okra to the Europe,” says a proud Somamalik, who is illiterate but has enrolled both his children at the local school.

Farmers benefited

Several other farmers of Mokhada have benefitted from collective farming. “There are over 650 vegetable farmers, 1,000 horticulture farmers and 200 floriculture farmers involved in collective farming,” informs Rahul Tiwrekar, lawyer and consultant with Aroehan. According to him, collective farming has increased the annual average turnover of subsistence farmers from Rs 5,000 per farmer to over Rs 85,000 a farmer.

Collective farming, locally known as gath kheti, is a type of agricultural production in which a group of farmers owning contiguous land engage jointly in farming activities and sell their produce as a joint enterprise in the market.

Since 2010, Aroehan is organising farmers to train them in collective farming. A group of 10 farmers pool their lands to begin group farming. In case a villager does not own land, a fellow farmer owning four to five acres lends a small portion to the landless villager against a nominal rent. For instance, Somamalik has taken 1.5 acres on rent from a fellow farmer, Vadu Sakru Bhau. “From my produce, I share 20 per cent with Vadu Sakru Bhau,” informs Somamalik.

Water for irrigation

Apart from land, availability of water for irrigation is an important factor for collective farming. Mokhada has negligible irrigation facilities because of which there is high migration in the rabi season.

“Khoch has a minor irrigation scheme lying defunct for many years. We spent over Rs 1,000 to fix a part of the broken underground irrigation pipeline so that some land can be brought under irrigation for collective farming,” informs Tiwrekar. Villages that lack irrigation facilities set up water harvesting structures or solar water lifting systems to grow the rabi crop.

The decision of crops under collective farming depends on factors such as local terrain, climatic conditions and the market demand. So far, Khoch farmers have cultivated okra, chilli, French beans, tomatoes, onion, ridge gourd, eggplant, etc.

Calculating costs

Initially, only half an acre land per farmer is brought under collective farming. Members of Aroehan, along with the farmers, calculate input cost per season in terms of seeds, manure and fertiliser, etc. “Roughly, half an acre land needs Rs 2,000-3,000 input materials. Aroehan provides this money as seed amount. It also links the farmers to the neighbouring APMC (Agriculture Produce Market Committee) markets in Vashi and Nashik,” says Tiwrekar.

Grazing cattle can destroy vegetable crops; hence crop guarding is crucial. “Collective farming helps as we guard our fields on shift basis. We also work at each other’s fields, thereby reducing the need to hire extra labour,” informs Vadu Sakru Bhau.

Once the crop is ready, all the farmers of the group hire one pickup truck to transport their produce to the APMC market, which saves money, says Madhukar Bhau, a farmer from Khoch. Interestingly, the farmers of Khoch recently bought a pickup truck from their group savings of the last few years.

On an average, an acre of land leads to an earning of Rs 40,000-50,000 per season. Thus, farmers growing two crops in a year get an annual average turnover of Rs 85,000 per farmer, informs Tiwrekar. According to him, some farmers in Mokhada have already received GAP (Good Agricultural Practices) Certification and are exporting their produce to the European markets.

Linking farmers to banks

As part of collective farming, Aroehan helps the farmers’ group open a joint bank account in which each member deposits a fixed amount on regular intervals. Khoch farmers, for instance, deposit Rs 100 per month per farmer. In times of need, they borrow money from the joint account and repay it after the sale of their produce. “We no longer borrow money from the local money-lender who used to charge us 50 per cent interest rate,” says Madhukar Bhau.

Over 300 farmers of Mokhada have also received the Kisan Credit Card (initial limit of Rs 95,000 per annum) from the IDBI Bank. They use this card to buy input materials for agriculture purposes.

Health benefits

Apart from the direct benefits of collective farming, there are several indirect benefits as well. For instance, farmers have built pucca houses and their children are regularly attending anganwadi and school. Palghar is infamous for malnutrition deaths. “The reason for high malnutrition in Palghar is lack of livelihood, which forces villagers to migrate. Collective farming can help address this problem,” says Abhijeet Bangar, collector of Palghar.

Somamalik agrees. “Our children are not malnourished because they regularly eat vegetables,” he says.

However, freak weather events are a matter of concern. Last year, Somamalik lost 1.5 acre of chilli crop due to untimely rains. This May, Vadu Sakru Bhau’s one-acre banana plantation was flattened by freak rainfall and high wind speeds. “I was expecting Rs 1.5 lakhs from the banana plantation, but barely earned Rs 10,000,” he laments.

But, had it not been for the collective farming, we, too, would have committed suicide like several other farmers of Maharashtra, he adds.

Nidhi Jamwal is a journalist based in Mumbai. She tweets @JamwalNidhi.