New print on the block

You know about Rajasthan’s Sanganeri and Bagru block prints, admire their imperfections and perhaps have a wardrobe full of them. But have you seen Jhag – the newest print in the collections of some of the reputed Indian handloom brands?

Jhag print is catching attention due to its more contemporary look, use of novel hues, and perhaps most significantly, the fact that it uses only natural pigments. The print – its name comes from the village in Rajasthan where it has been developed – is the baby of Prahlad Singh Nagar, who has been practising the art of block printing since childhood. The profession has been a family occupation for generations. Nagar’s two sons are also running their own businesses in the same field now.

The first signs of the work that Nagar is involved in are visible even before you enter his house. The edge of the road outside the main door of his house is streaked with brightly-tinted water, the turmeric yellow getting mixed with a dull maroon dye as the narrow stream wiggles its way down the street. Step into the courtyard and you realise what it means when they say there’s something charismatic about chaos. It’s an open-air theatre of colours – powders and liquids, watery and slushy, tainting the floor and the walls, and the hands and clothes of the artisans, and of course, yards and yards of fabric.

The dyes come from nature. Different types of soil, fruits, flowers, seeds, herbs and plant gum are used to prepare the concoctions, including tamarind seeds and flowers, pomegranate peels, indigo leaves, turmeric powder and multani mitti. Unique variations of the traditional colours are used in the motifs, created using carefully derived proportions of the ingredients, intensity and duration of boiling the colours, and the right combinations on the fabric, mastered through trial and error over the years. Alum is used as a mordant. Guar gum derived from cluster beans acts as a thickener. Horseshoe nails are used to get black dye, for which tamarind seed powder acts as the fixing agent. Peepal gum is used to obtain a pleasant pink dye. Alum gives red, as does kashish (potassium permanganate). Nagar keeps the proportions close to his chest. “My sons and I prepare the colours at home either early in the morning or late at night when the workers are not at the site,” he said.

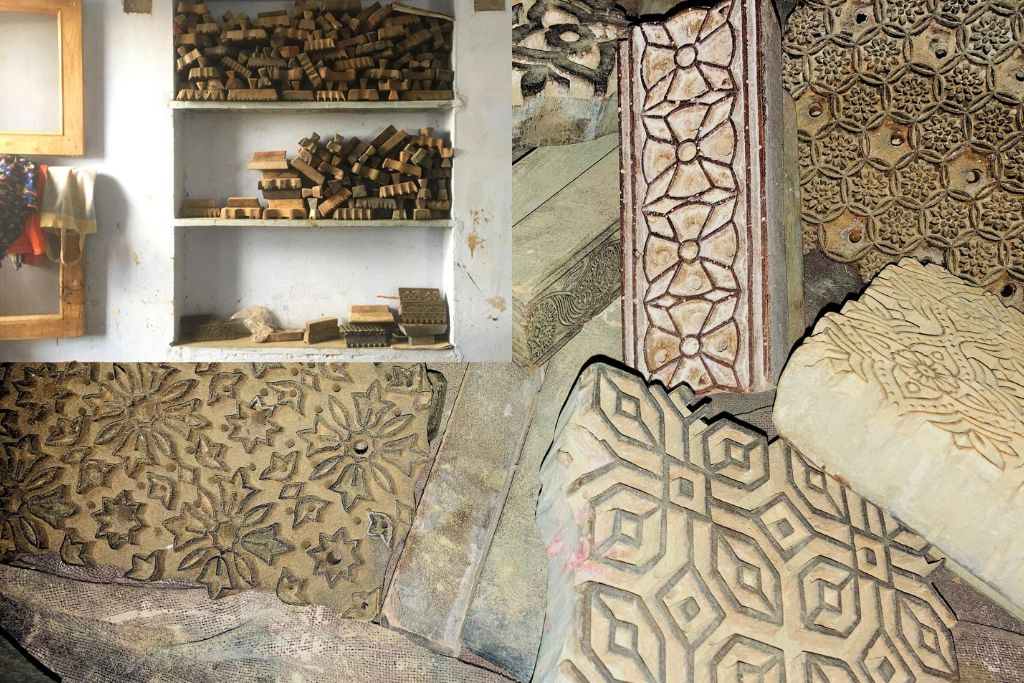

Traditional floral motifs used in block printing in the region have been reinvented. A designer in Delhi creates the patterns that are carved on wooden blocks by artisans, mostly living in Bagru. The blocks are made of sheesham, sagwan (teak) or rohida (Tecomella undulata) wood.

The fabric is procured from various places around the country. Cottons come from Tamil Nadu, silk from Chanderi in Madhya Pradesh or Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh. It is first washed thrice and then dyed using harda (black myrobalan) seed powder. This acts as a natural mordant, and gives a pale yellow base colour that makes it easier for other dyes to bind to the fabric. Then it’s left to dry before it’s printed further.

The workshop looks every bit unlike a factory. There is no fancy machinery here. Just long wooden tables that function as work stations. And carved wooden blocks strewn around. A small movable stool is where the tray containing the thick liquid colour is kept.

The actual process of block printing is tedious, requiring immense patience and concentration, not to mention a keen eye and strength in arms. It’s a hypnotic movement of sorts –the artisan dipping the wooden block in the concoction and stamping it on the fabric, motif after motif, uniform distance apart, thak, thak, thak… The process is repeated for each colour that has to be used in the design scheme.

After the block printing process is finished, the next step in line is giving the final polish to the fabric. A mixture made using gum and other ingredients is applied with a brush like the one used to polish shoes to give a final coating to the prints. “This gives a shine to the designs and also helps prevent the colour from running during a wash,” Nagar said.

The cloth pieces are washed in cold water to remove excess colour. They are then boiled in hot water in a huge copper pot. Alizarin – a red dye obtained from the roots of the madder plant – is added to boiling water to further enhance the colours.

Each piece of cloth is dyed according to the final outfit it has to be turned into. The motifs on the body or the borders are printed to size accordingly. The finished product is sold to the final customers by the big brands at three times the amount he gets.

A Jhag print product is also more expensive than the sundry cheaper versions you get in the market, all labelled as Rajasthani block prints. “Almost all of them are dyed using some percentage of chemical colours. That’s how you can get block-printed dupatta for only Rs 300,” Nagar said with a wry smile.

The lead image at the top shows block-printed sarees being dried on the terrace (Photos by Pallavi Srivastava)

Pallavi Srivastava is Associate Director, Content, at Village Square.