Where are women in local government?

Dismayed by seeing very few women in district-level government prompts two young development professionals to find out why.

Dismayed by seeing very few women in district-level government prompts two young development professionals to find out why.

The first thing that struck us about the administration of Chhatarpur district was the absence of women.

For a while we thought perhaps we had not seen the entire office. We assumed the women were at work in their rooms and that’s why we didn’t see them. But we didn’t see them in meetings either.

There were hardly any women among what seemed like a sea of men.

In the first few meetings we were the only two women. It always left us wondering why women’s representation in an office for the administration of the entire district was minimal?

Urban gender inequality, the absence of women in STEM, the struggles of women in rising the corporate ladder, the lack of women on boards and absence of women entrepreneurs are issues which are slowly but steadily getting highlighted in urban India.

But we rarely get to hear that there are few women gram rozgar sahayaks or sachivs or sarpanches – as employment guarantee assistants, the panchayat secretary or the panchayat president.

In the discussion about male bastions more often than not there is no discourse about employment in remote or so-called backward areas and government offices, like the district administration or the panchayat.

Yet, these offices ensure the implementation of all policies that administrators plan for everyone – male and female – at the grassroots level. But few women are decision makers.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG) encourages states to ensure women’s full and effective participation, never mind equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision making in political, economic and public life.

Another point prompts states to adopt and strengthen sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels.

But, according to the Global Gender Gap Report 2021 published by the World Economic Forum, India ranks 140 out of 156 countries. As per Census 2011, India’s population was 121.06 crore and the women constituted 48.5%.

For a country with so many women, the number of those in positions of power is dismal.

To find out why, we wanted to dive deep at the micro level.

The district (zilā), of which India has more than 600 each governed by a district collector or magistrate, is the fulcrum of all development.

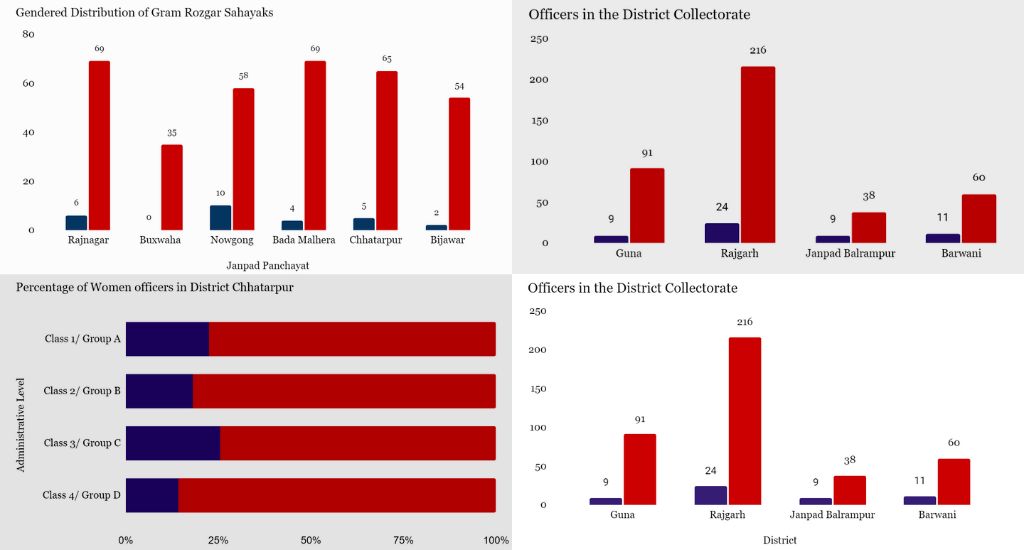

Analysing the number of officers working in the collectorate of four districts, we found that the maximum number of women work in Janpad Balrampur. But they form only 19.15% of the officers.

In Guna there are nine women and 91 men. In Rajgarh there are 24 women and 216 women. In Barwani, there are 11 women among 60 men. We found the lack of women’s representation evident and appalling.

Wanting to further examine the distribution of women, we collected data about the total number of government officers across classes in the entire Chhatarpur district.

Of the total 12,521 officers, the district has only 23.50% women. The highest percentage of women (25.39%) is employed as Group C/ Class 3 category while among Class 4 employees the representation of women is just 14.28%. Right from the lowest to the highest level, representation is inadequate and the government needs to actively take measures for its improvement.

Before we analyse the data about the panchayat secretary and employment guarantee assistants, we should understand how the decentralised panchayat system works.

In rural areas the gram panchayat is the first tier of democratic governance. The panchs or the panchayat members and the panchayat are answerable to the gram sabha because it is the members of the gram sabha who elected them.

This people’s participation in the Panchayati Raj system extends to two other levels – the block level, which is called the janpad panchayat or the panchayat samiti. The samiti has many panchayats under it. The panchayat secretary is also the secretary of the gram sabha. This secretary is not elected but is appointed by the government and is responsible for the gram sabha meetings, panchayat and keeping a record of the proceedings.

The employment guarantee assistant is responsible for assisting the panchayat in executing MGNREGA works. Both are last mile workers instrumental in all kinds of development work.

The streaming series Panchayat has made local government a point of focus and has helped us understand the role of a sarpanch, sachiv, secretary in ensuring that government programmes get implemented in the remotest of villages. In the show, the sarpanch, sahayak sarpanch, sachiv and assistant to sachiv are all men and that is not very far removed from the reality.

An analysis of the panchayats across the six janpads of Chhatarpur district sheds light on the extremely low number of women sachivs and gram rozgar sahayaks. For the position of sarpanch there is 33% reservation for women. So they are still visible but no such provision exists for the administrative positions.

Among 394 sachivs across the district, only 3.05% (12) are women. The total percentage of women gram rozgar sahayaks is a little more at 7.16%. There are 27 women as opposed to 350 men. In Rajnagar janpad, there are 84 male sachivs and only two women. Buxwaha janpad has 0% representation in both positions with no woman sachiv or gram rozgar sahayak.

As a country we lack representation and have narrow policies which do not cater to half the population. Women’s representation makes things democratic and brings diversity in decision making. If they are 50% of the population they should have an equal voice.

UN Women found that women’s involvement impacts decision-making in a positive way – with examples including better childcare in Norway and more drinking water projects in India linked to higher levels of women’s representation.

In 2014 the International Parliamentary Union (IPU) undertook research that proved that the increased presence of women had an impact on pushing issues like violence against women and women’s health onto the agenda. Other studies highlight positive impacts on issues relating to women’s work, finances and equality under the law.

The IPU also found that the increased number of women in politics encourages women to contact their own representatives and participate more as citizens.

“Gender equality is at the core of an inclusive and accountable public administration,” according to the 2021 report of the UN Development Program, Gender Equality in Public Administration.

Ensuring equal representation of women in bureaucracy and public administration improves the functioning of the government, makes it more responsive and accountable to diverse public interests, enhances the quality of services delivered and increases trust and confidence in public organisations, the report found.

There is a long way to go in achieving gender equality, but we need to start at the very grassroots.

Promoting women to be at the last mile of our administration, in gram panchayats and district administrations, can help us increase their numbers.

We as a society need to be aware that the gender gap is vast, especially at the smallest units of administration and it won’t decrease unless we do something about it.

The image at the top shows lack of women involvement in government offices apparantly increasing the gender gap (photo by Rahul Raman).

Smriti Gupta and Sohinee Thakurta are Aspirational District Fellows in Chhatarpur, Madhya Pradesh.