Using puppet power to spread messages

Thol paavai koothu, the long but fading tradition of leather puppetry in Tamil Nadu, is reinventing itself by bringing awareness about the declining number of small animals and the importance of conservation.

Thol paavai koothu, the long but fading tradition of leather puppetry in Tamil Nadu, is reinventing itself by bringing awareness about the declining number of small animals and the importance of conservation.

It was chilly at 7pm in the hillside Nathanchedu village in the last week of March. The villagers – who would normally go to sleep early – came to the meadow, covered in blankets.

A vehicle loaded with puppets, speakers and musical instruments had travelled up the winding roads and had just arrived at the village in the Eastern Ghats near the popular hill station Yercaud in Tamil Nadu.

It was an announcement about a thol paavai koothu puppet show that brought the villagers to the meadow, foregoing their sleep.

The shows are organised by Brawin Kumar, a researcher at the Indian Institute of Science, Education and Research who studies rare mammal species in the Eastern Ghats, such as rock rats and hedgehogs. Through the paavai koothu performances he hopes to create awareness about the conservation of these mammals, which are crucial to the ecosystem.

(ALSO READ: Conserving endemic small mammals)

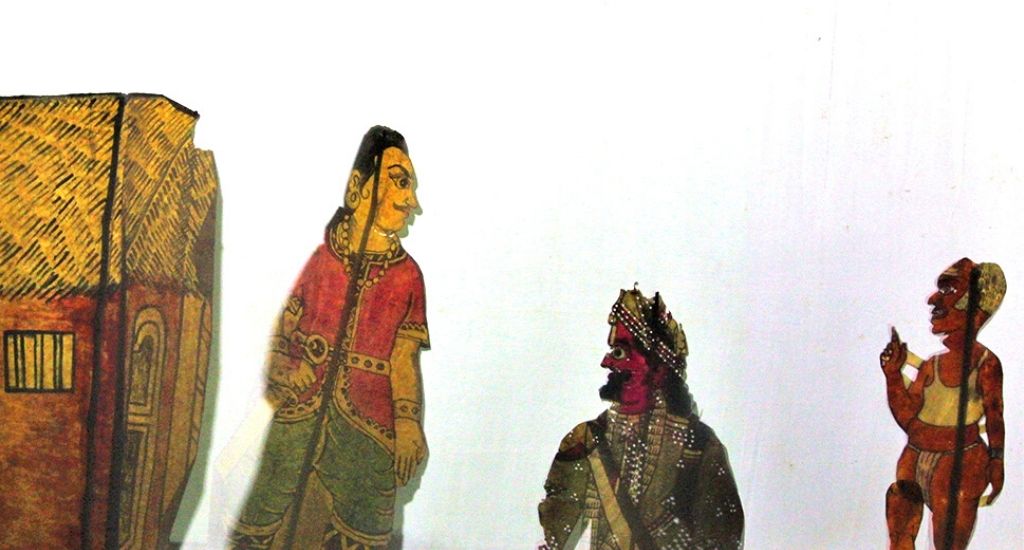

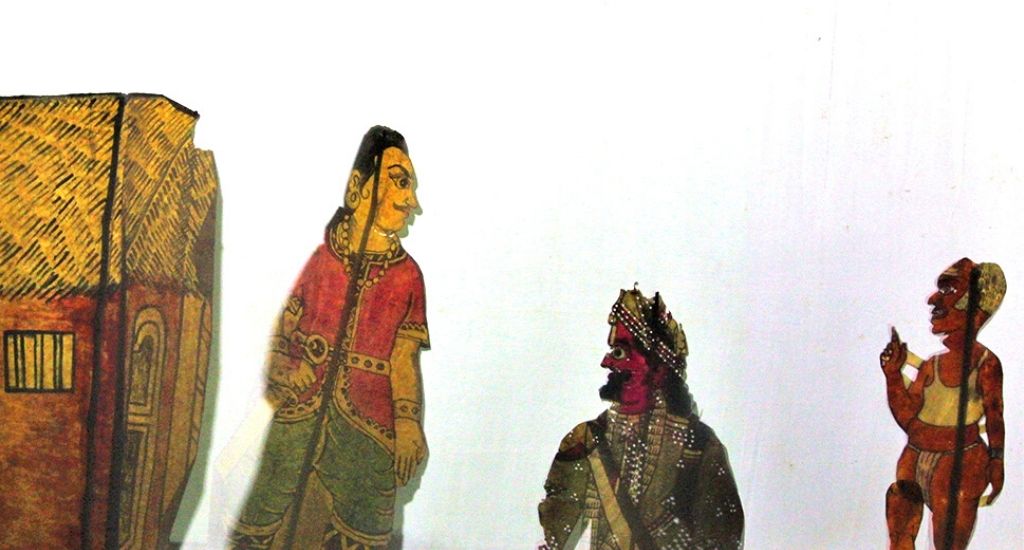

Thol paavai koothu is the traditional leather puppetry of Tamil Nadu. The three words literally translate as (animal) skin, doll and theatre.

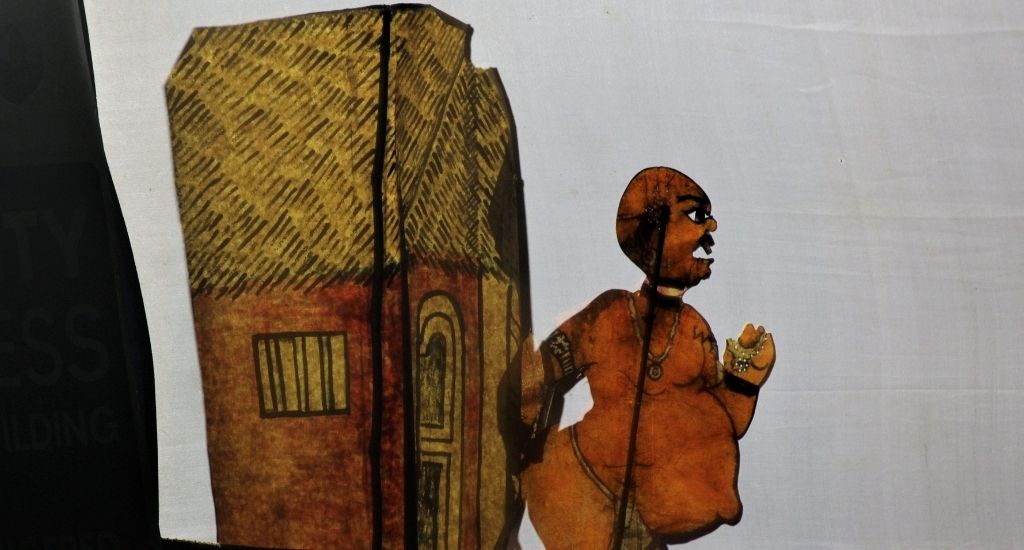

The traditional storytelling medium uses figures made from goat skin. The characters of the puppetry shows are sketched on processed goat skin and then painted with special paint.

“We add gum to the paint so that the puppets don’t lose their colour over time,” said A Lakshmana Rao, an artist who had come from Nagercoil to produce the show.

The stories use a combination of dialogues and songs, to the accompaniment of musical instruments.

Traditionally, the puppet shows were stories from the Ramayana and other epics. Today many shows come with more modern messages.

In Nathanchedu as the young and the old settled down, the puppeteers got behind the stage – simply a white cloth stretched between poles. The musicians, Rao, his wife and daughter, sat on the floor in front of the screen.

The audience perked up as the puppeteers tested their drum and harmonium. And then the animal figures popped up.

The story begins with a king checking on the health of wildlife on his land. He finds the animals suffering the consequences of human acts, like plastic pollution.

He summons his ministers to travel the land and talk to people about the importance of conserving the local species.

Both children and adults watch with wide eyes through the half-an-hour puppet show, with different animals popping up behind the screen.

Comedy is an integral part of thol paavai koothu and the audience laughs in delight.

But it is not just entertainment.

Crucial issues are covered in an engaging manner, from the impact of hunting practices to dumping waste into lakes and rivers and animals being killed by cars whizzing down the roads.

One after another various local species are portrayed, such as porcupine, wild squirrels, rock rats and rabbits.

The audience is enthused about the story and contemplative about conservation.

When Brawin Kumar wanted to build awareness among tribal school children and villagers in the Shevaroy Hills, he was told to use thol paavai koothu.

“The thol paavai koothu artists had already done programmes with NGOs on vulture conservation. I thought it would be interesting to communicate conservation with our traditional puppetry,” Kumar told Village Square.

“During the pandemic these artists had no income. Using thol paavai koothu would help the artists as well as have an engaging outreach programme for conservation.”

Kumar discussed and developed the story with Rao, who had done a few programmes on saving the environment and biodiversity.

I thought, we always do history, why not do something on wildlife? I took it as a challenge and scripted the story.”

“I thought, we always do history, why can’t we do something on wildlife? I took it as a challenge and we scripted the story together,” said Rao.

“The painted animal puppets were done in about 20 days,” he added.

Rao, his wife Nagarani and daughter Kalai Rani lend their voice to the story and sing. His son, Muthuvel, takes the centre stage by mimicking various voices.

Of the four sons of Rao, Muthuvel has decided to follow Rao’s footsteps.

“As a family, we artists function as a unit. From playing percussion and harmonium to painting and making puppets, to mimicking, it is all within the family,” said Rao.

“We have scripted, directed, brought in comedy scenes, even songs for this programme,” he said.

Nagarani reminisced about setting up tents for performing thol paavai koothu when there were no televisions.

“People crowded inside the tents to watch our puppet shows,” she said. But the art form has lost out to modern entertainment. (Also read: Indigenous art forms of Santhal Pargana are in need of revival)

Muthuvel believes that government and private organisations could rope them in for more awareness programmes and thus support their livelihood.

“Our art is fading. These animals are also vanishing from the lands. We want to give a life to these animals and also to our art through such programmes,” concluded Rao.

The lead photo at the top of this page is by Sharada Balasubramanian.

Sharada Balasubramanian is a Coimbatore-based journalist.