‘Urban’ LGBTQIA+ versus queerness in rural India

Legalising homosexuality has had little impact on the deeply entrenched queerphobia in rural India, where there is a lack of awareness and discussion on LGBTQIA+ rights.

Legalising homosexuality has had little impact on the deeply entrenched queerphobia in rural India, where there is a lack of awareness and discussion on LGBTQIA+ rights.

Ayush Kadsholi from a village in the Himalayan state of Himachal Pradesh avoids public urinals because of the relentless bullying they faced as a child.

Gurleen from rural Punjab remembers an uncle’s angry abuse for being “unfeminine” when she got her hair cut to a short crew – as most schoolboys do. She identifies herself as non-binary.

Awara felt unwelcome, left out, and let down by a predominantly suave, savarna, English-speaking urban LGBTQIA+ crowd at the 2022 Pride parade in New Delhi and had often run into situations in such “elite queer” circles where her presence wasn’t appreciated. The 26-year-old from Delhi is a Dalit queer person.

Khwaish* (name changed to protect identity) knows all too well how entrenched is the varna or caste system in the queer circuit, a part of the bigger LGBTQ+ community that itself is on the margins of society and suffers from every institutionalised form of hatred and exclusion.

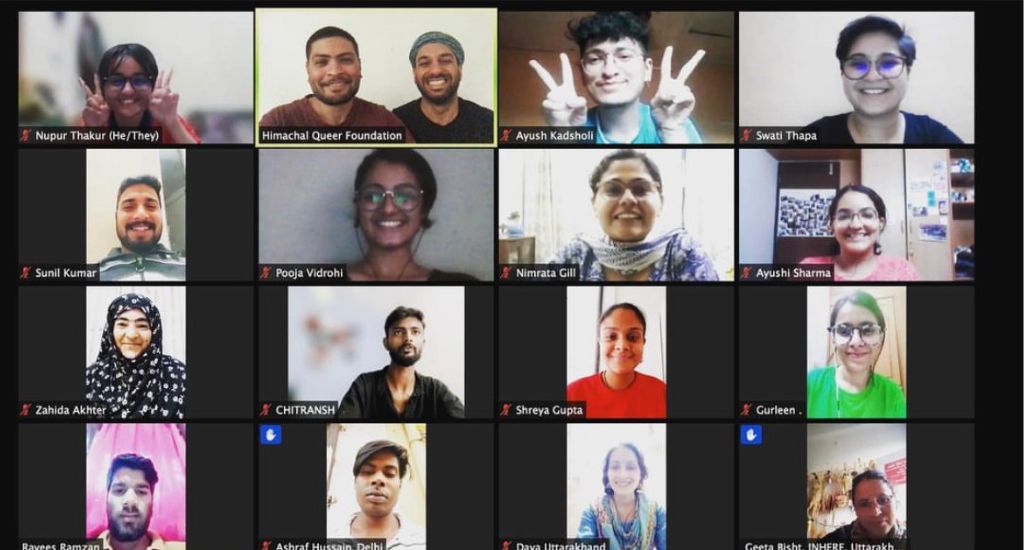

Khwaish is an Adivasi queer person from Madhya Pradesh and a gender fellow with the Himachal Queer Foundation, that works with the queer community in rural India.

Also Read | Being LGBTQ in rural India

“It becomes much more difficult. You’re always on the run from something. I had to flee from home, flee from marriage, flee to study, and then flee strange gazes at my queerness. There are far too many hurdles,” said Khwaish.

An unhinged urban-rural partition and social praxes such as caste identity have pushed people from the queer community in India’s vast countryside and small towns to feel more insecure in a nation where homosexuality remains taboo.

Newfound openness is visible only in big cities after the Supreme Court struck down in 2018 a colonial-era law that criminalised gay sex. The country staged its first “Queer Pride Parade” in Delhi in 2008, and has done so every year since.

It becomes much more difficult. You’re always on the run from something. I had to flee from home, flee from marriage, flee to study, and then flee strange gazes at my queerness.

India’s first gay products store, Azaad Bazaar, opened in Mumbai, as did the first gay online bookshop, Queer-Ink.com. Gay beauty contests are being held regularly, although the government said in the Supreme Court recently that appeals to legalise gay marriage are “urban elitist views”.

Dalit queer person like Awara believes “elitism” within the LGBTQ community and the absence of important issues of intersectionality pertaining to caste and social inequality may present a bigger barrier than a largely conservative society in securing equal rights for queer people.

“I went to the Delhi Pride Walk…couldn’t find anyone who looked like me. All were dressed in their best and spoke English. I felt like a misfit. But that didn’t stop me from celebrating who I am,” said Awara, whose name means vagabond, a word that encapsulates her gung-ho persona.

Family relationships play a crucial role in the well-being of, but parents and relatives often fail to understand why the kid is acting or appearing in gender-non-conforming ways.

“My uncle once confronted me and said women who keep their hair short are of loose character. Another time, he and I had a little debate on marriage. His daughter later wrote in the family WhatsApp group that I was disrespectful. They unfriended me,” said Gurleen.

Also Read | Not all rainbows for trans people in Mizoram

Being non-binary is not easy, especially in small communities. It gives sleepless nights, there is constant pressure to get married and many friendships and family relationships get ruined.

“I was seen as a problem child because I questioned my parents and everyone around me. I knew I didn’t align myself as a cis woman but I also knew coming out to my family was never an option on the table. I wore salwar suits, kept my hair long, nails long and polished, suppressing my non-binary identity,” Gurleen said, recalling her struggle with her gender identity and the lie her life had been.

Gurleen’s story resonates with people who live in small towns and villages.

Ayush Kadsholi of Himachal’s Shimla district couldn’t fit into a heteronormative existence as a child. “The boys would ask if I am a boy or a girl. Many students would ask me to join their brothel where I would give services. Back then I had no other answer so I would just laugh,” he said.

Public sentiments are ambiguous in rural India, where traditional values often clash with gender and sexual expression outside the gender binary norms. People’s ignorance, compounded by misinformation, pushes non-binary children into unrelenting bullying and harassment.

Ayush recalls that a student had asked the teacher in his Class 11 biology class “What is a gay person?” and was told that it was “some error in their chromosomes”.

Ayush dreams of living a simple, dignified life that would allow him to leave, even forget, the humiliation and fears of adolescence, and the slurs his mind still carries.

There is no official data on the LGBTQIA+ population in India, but the government in the past has submitted to the Supreme Court that the nation has an estimated 2.5 million queer people. The numbers don’t reflect many individuals – especially those in rural India – who conceal their identity fearing discrimination.

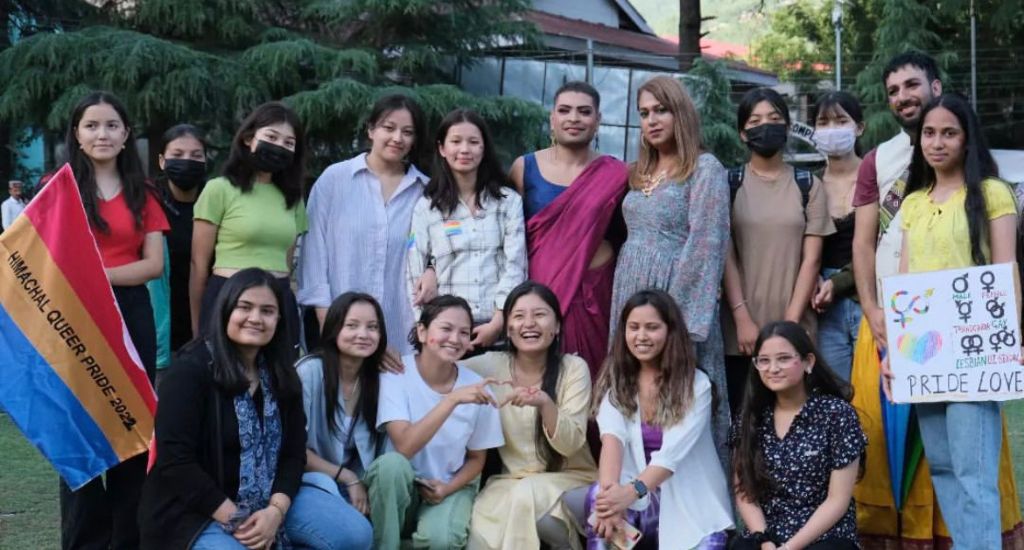

The lead image at the top shows the pride parade celebrating LGBTQ+ with flags and banners (Photo by Himachal Queer foundation)

Swati Thapa is a freelance journalist currently based out of Almora.