The 15,000-odd inhabitants of Mahud-Badruk village — wracked by recurrent droughts, increasing dependence on tankers for drinking water in summer, shrinking farming acreage due to paucity of irrigation facilities and falling livelihood income — had for long nursed a dream of reviving the 5km long Kasal odha or rivulet.

Kasal rivulet made its presence felt when it rained, which is a rare event, said the villagers. According to the villagers, it rained heavily this year and not a drop was wasted since they had deepened and desilted the riverbed ahead of the monsoon.

The initial steps to address the water stress began in May 2016. The efforts culminated two years later, with Mahud judged as the Best Village Panchayat of 2018 and conferred with the National Water Award that included a citation and Rs 2 lakh cash component.

The villagers’ initiative that ushered in active participation of the local people, district officials and a few corporate entities who donated generously for the water conservation project, is being hailed as the Mahud pattern. Revival of Kasal has led to increased groundwater levels and cultivation using drip irrigation.

Drought-prone district

Located on the Pandharpur–Karad Road, Mahud in Sangola taluk of Solapur district, is in the rain shadow area of Maharashtra. Hence, Mahud and all the villages in the district are prone to perpetual water scarcity.

The average precipitation in Solapur district is roughly 488mm, the monsoon period being June to September. It has one of the largest areas covered under Drought Prone Area Program (DPAP) in Maharashtra, with ten administrative blocks covering about 13,730 sq. km area.

As per the National Agricultural Research Project (NARP) classification of agro-climatic zones of the country, Solapur falls under the MH-6 scarcity zone. Though Mahud has a cultivable land measuring 4,856 hectares, 500 hectares remained uncultivated due to lack of irrigation facilities.

Villagers’ contribution

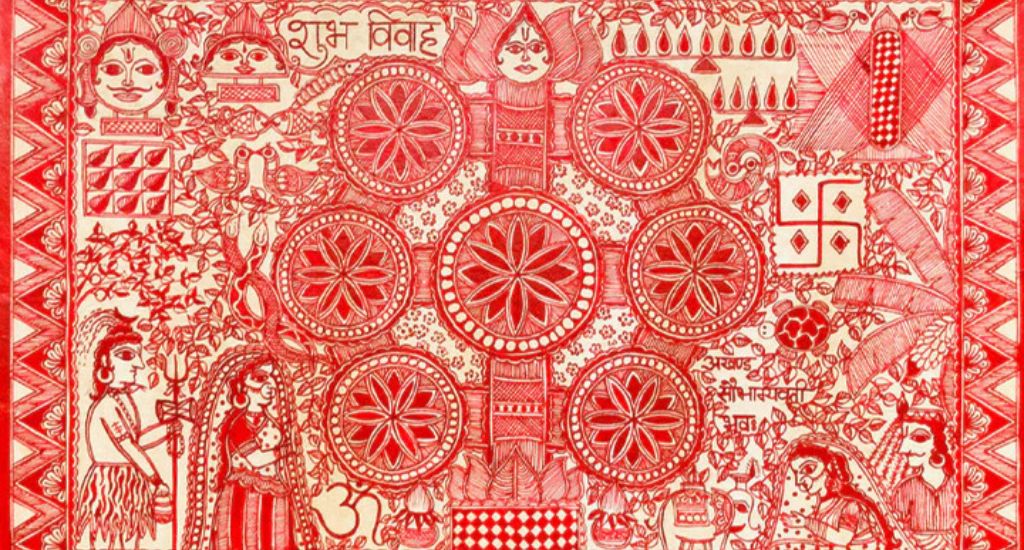

Awareness through processions, singing of bhajans and kirtans, campaigns in schools and workshops for women’s self-help groups on issues relating to water conservation and tree plantation became a daily affair in Mahud.

“We began by involving the local people in raising awareness and the requisite funds to revive the rivulet,” Mahendra Mahajan, a correspondent of Sakal, a Marathi daily, and a native of the village, now settled in Nashik, told VillageSquare.in.

To address the issue of water stress, Mahajan mobilized the villagers and brought government officials on board for the rejuvenation. “Every villager be she a gram panchayat member, student, homemaker, farmer, shop keeper, and even those who came for Datta Jayanti Mela, donated generously,” he said.

With individuals donating between Rs 1,000 and Rs 10,000, the Mahud gram panchayat raised Rs 10 lakhs within a week. “Even the district irrigation department officials donated two days’ salary towards hiring of earthmovers and diggers,” Balasaheb Dhakle, sarpanch of Mahud, told VillageSquare.in.

Riverbed widening

Over the years the size of the rivulet has been shrinking due to encroachment of its banks. The situation began in the mid-seventies when the district witnessed its maiden cycle of drought that continued in the subsequent years too.

“In several places, the width of the rivulet was as narrow as 10 meters,” J Mahamuni of the district water department, told VillageSquare.in. “However following an appeal from the district collector, the encroachers vacated voluntarily. And now the odha has been widened to 100 meters.”

Ripple effect

With earthmovers put to work, the excavation and desilting of the 5 km long stretch were completed within two-and-a-half months. Farmers who had barren lands used the large volume of excavated soil in their farms. When the monsoons arrived, the deepened rivulet flowed to its full, raising groundwater table.

Soon residents of villages downstream too joined in, leading to the desilting of an additional 43 km long stretch. This would benefit 23 additional villages in Pandharpur and Malshiraj taluks with a total population of 77,000 people.

The rejuvenation of 48 km long rivulet cost Rs 9 crore, of which Rs 6 crore came from the Tata Trusts and Rs 60 lakhs from the CSR funds of Jawahar Lal Nehru Port Trust, routed through the Art Of Living Foundation. Individuals, NGOs and charitable organizations contributed the rest.

Agriculture revival

Everyone in Mahud, be it a doctor, lawyer, jeweler, shopkeeper or a school teacher, has a farmland of his own, ranging from 2 acres to 30 acres. Mahud’s farmers majorly grow pomegranate, jowar, bajra and ber or Indian jujube.

Despite being in a semi-arid zone, Solapur has the largest number of sugar factories in the state. About 71% of the irrigated area is under sugarcane production. Ujani, one of the largest reservoirs in the state, falls in Solapur district, giving a spurt to water-guzzling sugarcane farming.

Dattaraya Shankar Nagne, who spread the excavated soil on his 5-acre barren land has planted pomegranate after the rivulet was filled post monsoon. With the revival of Kasal, many have started growing sugarcane too, but with all crops being drip irrigated.

New ecosystem

During the two years that the revival work happened, beginning 2016, over 25 lakhs saplings were planted on the rivulet’s banks. Rajendra Singh, Magsaysay awardee and water conservationist, was supportive of the rivulet rejuvenation, addressing villagers and participating in the tree plantation drive.

Rejuvenation of Kasal rivulet has led to the ushering of a water-friendly ecosystem that includes creation of 250 farm ponds, building of minor and large irrigation systems, raising of stream bunds which replenish aquifers, and recharging of bore wells.

The initiatives have led to a rise in groundwater levels. “Gone are days when we used to queue for the water tankers to arrive during the summer months,” Mahajan told VillageSquare.in.

Hiren Kumar Bose is a journalist based in Thane, Maharashtra. He doubles up as a weekend farmer. Views are personal.