What’s curdling the milk in Uttarakhand?

Most people are finding it hard to keep even one cow as milk yields are getting lower, finding natural fodder is becoming extremely difficult, and feed prices are soaring beyond their reach.

Most people are finding it hard to keep even one cow as milk yields are getting lower, finding natural fodder is becoming extremely difficult, and feed prices are soaring beyond their reach.

A milk collection point for four hillside villages in Uttarakhand’s Nainital district serves more than its intended purpose. It’s a haunt where villagers of Reetha, Odakhan, Meora and Nathuakhan gather and put the world to rights while emptying their milk cans into containers of the Uttarakhand Cooperative Dairy Federation (UCDF).

The day’s collection fills up around 10 big cans, each containing 30 litres of either cow or buffalo milk. These are then ferried by mini-trucks of the milk cooperative to its processing unit in Bhowali, around 40km away. The packaged milk and other dairy products are sold under the brand name Aanchal.

All looks well, but not exactly. Dairy farmers are facing challenges that are squeezing their income. Among the causes is low solids-not-fat (SNF) in their milk.

“The SN in the milk of our cows has gone down,” said Ganesh Bisht of Harit Patti in Nathuakhan village, who owns two Jersey cows. SNF consists of protein, carbohydrates, and minerals. These along with fat play an essential role in enhancing the shelf life of dairy products such as sweetmeats.

The SNF value determines the price of milk. Suresh Raikwal of Odakhan delivered two litres of milk at the depot but gets only Rs 36 a litre because of the low SNF content. The farmers earn between Rs 35 and Rs 40 a litre. With better SNF, the price can go up to Rs 50 a litre, which is possible only if the cattle get “supplements and fortified fodder”, said Ganesh Bisht.

“All these cost about Rs 1,700 a month for each cow. Add in the expenses for veterinary care and miscellanies. The upkeep cost for a Jersey cow reaches Rs 2,000 a month,” he said.

A cow produces an annual daily average of three litres of milk – ranging from six a day in its prime to no milk in the last trimester of its nine-month pregnancy. The earning comes to around Rs 40,000 a year. After deducting the rearing costs, the net annual income comes to about Rs 16,000. State subsidies of Rs 5,000 annually make a tiny difference to the wallet.

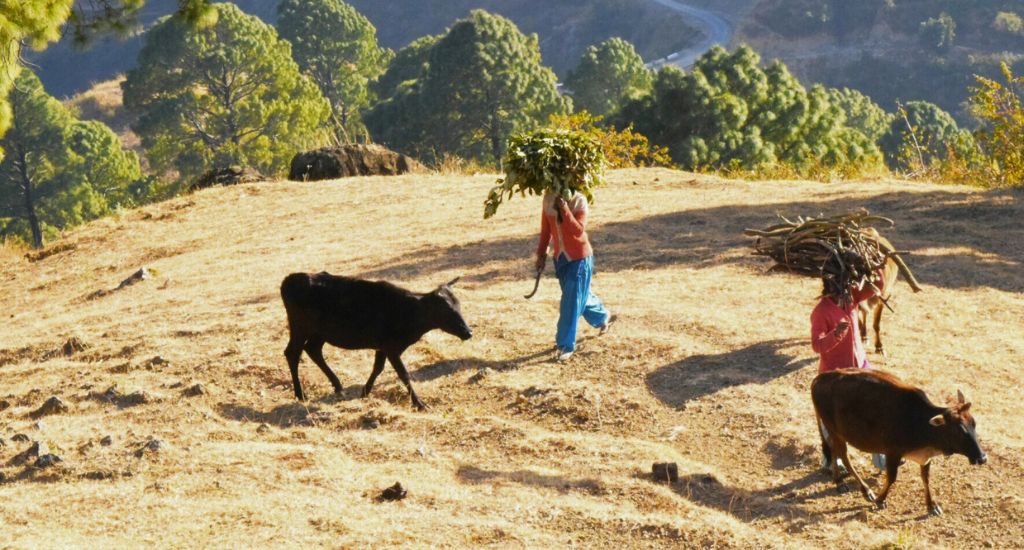

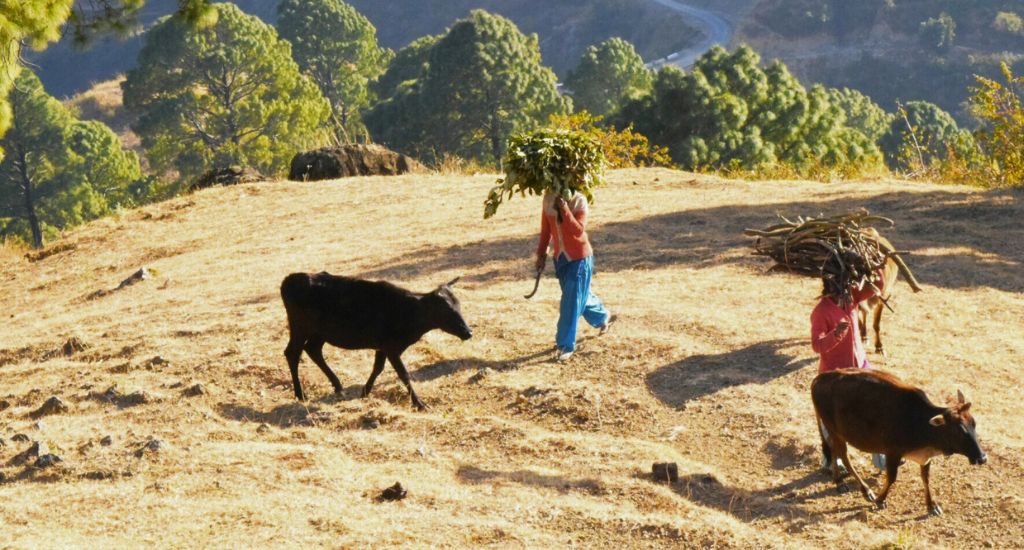

Still, each family owns a few cows and women typically take care of the livestock. Hordes of women are seen scouring the forests for fodder. But there’s little grass to be found as more and more open spaces give way to housing, forcing livestock owners to buy expensive feed. The price of hay had doubled to Rs 1,200 a quintal in the past four years.

“It makes sense only if the price of milk is above Rs 60 a litre or if the state subsidy on raw materials is at least 50 per cent,” Ganesh Bisht said.

Sensing the farmers’ anxiety, the Nainital arm of UCDF increased the price of milk by Rs 8 in two instalments since March 22. “For us to get Rs 60 per litre, Aanchal will have to sell the full cream milk for Rs 80 a litre,” Ganesh Bisht said.

Rearing cattle is part of the tradition in the meadow-dotted mountainous countryside of this Himalayan state. “Hermits had only milk all their life and lived long,” said Devi Singh Bisht, a milk collector of the cooperative.

But rearing cattle has become ungainly. Farmers mostly buy Jersey cows from the foothills for around Rs 70,000 each. They take bank loans and the monthly instalments eat up a large chunk of their income.

“Many abandoned the business because of thin margins. Milk collection has also become expensive due to increased diesel prices in the past few years,” Devi Singh Bisht. “Cooperatives and the government have to launch awareness campaigns about new cattle breeds,” he said, suggesting the promotion of organic milk and local breeds, such as the Pahadi cow that produces A2 milk.

At the same time, people don’t know what to do with their old, unproductive cows – most of whom are abandoned and they amble around villages as strays. Most states have long outlawed cow slaughter, but a crackdown on the trade of cattle in recent years had hit the rural economy, said farmers who revered cows as most devout Hindus would.

“I had to give away my productive Jersey cow to my brother-in-law because I didn’t know what to do with it when it gets old,” said Dharmendra Pandey of Kokilbana village, who teaches Sanskrit in a government college near Bageshwar and is also a sought-after priest in the area.

There are growing calls for the government to come up with more cow shelters and let cattle traders deal in other animals without fear of attack by cow vigilantes.

Pandey bought a buffalo, which is costlier but produces less milk and can be sold off when the need arises. “This trend will lead to an overall dip in milk production and availability, making cow milk costlier,” said Devi Singh Bisht.

The lead image at the top shows women grazing cows at a village in Uttarakhand (Photo by Ashutosh Rawat via Wikimedia Commons)

Anurag Tomar is a former journalist who now lives in a village in the Uttarakhand hills.