UP’s young water evangelist

A young woman receives international recognition for her work ensuring 22 UP villages - and counting - get clean, safe water and learn how to fight against contamination.

A young woman receives international recognition for her work ensuring 22 UP villages - and counting - get clean, safe water and learn how to fight against contamination.

The sight of people wasting water – even when it’s readily available – hurts Ramandeep Kaur so deeply that she can’t keep quiet.

“I hold water sacred and recognise its role in everything we do,” she said. When she sees someone washing dishes or clothes while keeping the tap water running, “I ask them not to waste it,” she said.

Seeing water polluted or becoming contaminated equally upsets her.

She is only 29 years old, but she is dedicating her life to helping people get access to clean water.

In July 2021 the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) honoured Kaur of Uttar Pradesh, along with 41 other women, as a ‘water champion’.

It’s not that Kaur’s village of around 3,000 people is short of water.

In fact Palia Tehsil in the Lakhimpur Kheri district lies in the Terai belt at the foothills of the Himalayas. The Sharda River basin enriches the groundwater, which is not only consumed by the villagers but used to water their fields as well.

Despite being available in plenty, the sight of people wasting this precious resource turned Kaur into a water evangelist.

“I see water as the provider of life and can’t bear the misuse of it,” she said.

What started as urging neighbours not to waste water grew into a more organised mission for Kaur, campaigning for better water governance in her area.

With her agriculturalist father’s support, she resisted the pressure to get married as a young teen.

She joined a local college as a private student and subsequently completed her post-graduation in social sciences.

To pay her own fees, Kaur bicycled 14 km daily to work for an NGO promoting the education of girls. This work gave her a great appreciation for the importance of education, which she would use later in her work among villagers.

In early 2019 Kaur joined Oxfam’s Transboundary Rivers of South Asia (TROSA) project. TROSA helps the poorest communities along the Sharda River basin alleviate poverty and manage their water resources.

TROSA partnered with Grameen Development Services, a local NGO working with communities dependent on the Sharda River for livelihood, to work on water issues.

Unfortunately, the groundwater in the district not only has high levels of poisonous arsenic, but other contaminants are found beyond the permissible limits, like fluoride, which in excess can disable people for life.

Six villages around Bajaj Hindustan Sugar Ltd have reported cases of skin ailments, the premature death of cattle and crop blight.

Yet the locals are wary of discussing water contamination, as most of them are sugarcane farmers with their livelihood dependent on the sugar mills.

But that did not stop Kaur.

“Initially we began a door-to-door campaign, making women understand the importance of safe drinking water,” said Kaur.

This was not easy for several reasons. Firstly, in the patriarchal set-up stepping out of the house is taboo for women. But also most of the women had never attended school and could not count beyond 20. A dark reminder about Lakhimpur Kheri’s literacy rate being a dismal 48.39%.

“They were so poorly informed,” said Kaur.

But she persisted and eventually the women began to understand the importance of clean water and good governance around this vital resource.

She not only educated the women but the entire community.

Kaur and her team soon reached out to the people of 20 other villages within a 40 km radius.

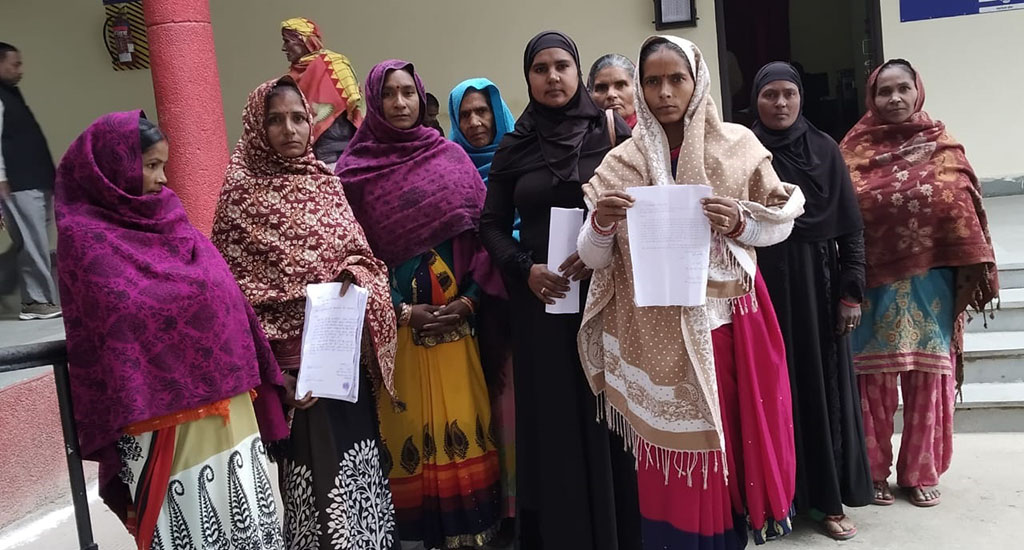

Each village formed its own ‘water vigilance committee’ composed of both women and men.

These committees met once every three months and deliberated on issues like the water quality from hand pumps to rising incidents of skin diseases, death of fish in the Sharda River and crop blight due to contaminated groundwater.

They presented these issues to the officials at the weekly tehsil diwas, a grievance redressal system.

Kaur and her team then helped set up the Village Water Management Committee (VWMC), which has gone on to pinpoint the impact of the private sector on local water bodies.

VWMC’s year-round observation and data showed very high contamination during monsoon. This was when the sugar mill released its untreated effluents in the canal leading to the Sharda River.

Now, many villagers are given water-testing kits to check the contamination levels, which makes them feel empowered.

“We regularly check the quality of both ground and surface water at three places before and after the monsoon,” said villager Urmila Prajapati.

Farid Ahmed, who found water contamination in the fields of Bijoria village, understands the dangers such toxins bring. But he is grateful to know what can be done to try and stop such contamination.

“We are now more aware. We also know about the different policies and initiatives of the government for rural poor,” he added.

In August 2019 the National Green Tribunal pulled up the sugar mill following a Central Pollution Control Board report, which stated that the distillery “was not fully compliant with the pollution control norms” and levied a fine of Rs 58 lakh.

Kaur and her team have taken their work to the next level in addressing water contamination. They formed the Sharda River Citizens Committee, by bringing all the VWMCs together.

Following concerns from the Sharda River Citizens Committee (SRCC) about water contamination, the district authorities cleaned the canal. But they didn’t concretise it to control seepage and stop contamination of groundwater, as the citizens had petitioned for.

However, the relief came in 2020 when the National Water Commission set up 21 overhead water tanks in 16 panchayats to supply drinking water.

Climate change is also affecting several villages, with the breaching of the Sharda River banks and land being eroded. After heavy flooding last year, crops were destroyed and homesteads were washed away.

To avoid the loss of food and livestock, the VWMC provides early warning messages to those living close to the river.

The VWMC gets the information about the rise in the water level from officials manning the Banbasa Barrage in Uttarakhand.

“The villagers receive the message almost 10 hours before water is released from the barrage,” said Sandip Nishad of SRCC. “That’s time enough for the villagers to save their valuables and escape to higher elevation.”

Hiren Kumar Bose is a journalist based in Thane, Maharashtra. He doubles up as a weekend farmer.